Growing up, the family members I knew and saw on holidays were almost entirely the descendants of one man: Antonio Luigi Saviano.

Most of us didn't know his name. He was the father of our grandparent or great grandparent.

But four years ago my mother pulled out a photo of Antonio lying in his coffin. He died in the Bronx, New York, several years before she was born.

|

| Was my first immigrant ancestor a shrewd businessman? |

I'd been researching my family tree for about 10 years at that point. The branch of the family where I'd made the least progress was Antonio's branch—the very branch I'd known my whole life.

This year I went on a quest to find out where Antonio and his wife Colomba Consolazio came from. Here's what I knew already:

- According to his World War II draft registration card, their son Semplicio was born in Tufo, Avellino, Italy.

- I had looked at microfilm of vital records from Tufo. I found Semplicio's birth and the earlier birth of a son—Raffaele Vitantonio Saviano. I knew this baby did not survive because it was a younger Raffaele who came to America in later years.

- Antonio and Colomba moved less than 10 miles from Tufo, Avellino, to Pastene. Pastene is a small section of Sant'Angelo a Cupolo in the neighboring province of Benevento. They had 3 children there: my great grandmother Maria Rosa, Raffaele, and Filomena.

- It was in Pastene that Maria Rosa met and married my great grandfather, Giovanni Sarracino. They had their first child there, but he did not survive.

- Antonio began travelling to America in 1890, three years after the birth of his youngest child. He was my first ancestor in any branch to do so.

- He was 47 years old at the time. That's a bit on the old side for the first of his three cross-Atlantic trips.

- He brought his son Semplicio to America and left him there. Then in May of 1898, Antonio returned to the Bronx with his wife and his children Raffaele and Filomena.

- The family left for America one month after the marriage of my great grandparents. That means my great grandmother did not have her family there to support her when she gave birth to her son Carmine in December 1898. And she didn't have their support when Carmine died a short time after.

Let's stop there for a moment. Something strikes me about my great grandparents and their ill-fated baby boy, Carmine.

Maybe my great grandparents never planned to come to America. Baby Carmine was born just shy of eight months after their wedding. There was nothing stopping them from coming to America with the rest of the family.

Maybe it was only the shock of Carmine's death, and his possibly premature birth, that drove the couple to leave their home.

Maybe if Carmine had lived, I would be an Italian national.

That aside, let's look at what I learned about my great grandparents Antonio Saviano and Colomba Consolazio this year.

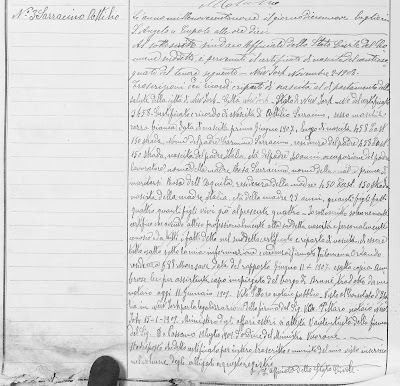

Working backwards from the Tufo births of their children Semplicio and the first Raffaele, I discovered that Colomba had two brothers living near her in Tufo. I found the marriage record for one brother.

His place of birth, and the town where his parents still lived, was not Tufo. It was the neighboring town of Santa Paolina.

My next step was to view microfilm of the vital records from Santa Paolina. Sure enough, I discovered that Antonio and Colomba were married there. They had a baby girl before Raffaele and Semplicio named Maria Grazia. She died after four days.

Colomba was born in Santa Paolina, but her real name was Vittoria Colomba. I learned her parents' names and her grandparents' names.

And on their marriage documents I learned the origin of my great great grandfather, Antonio Saviano. He was not born in Santa Paolina where he married and began his family.

He was not born in Tufo where he moved and had more children.

He was born in Pastene! The very town to which he returned, had more children, and from which he left for America.

Antonio Saviano, my first ancestor to come to America, travelled in lots of circles. He went from Pastene to Santa Paolina to Tufo to Pastene, completing a very small circle. He went to America and back to Pastene three times. Finally, he brought his family to America and settled down…age of 55!

Antonio lived to be 82 years old. He outlived his wife Colomba by five years, but he died surrounded by this four surviving chlidren.

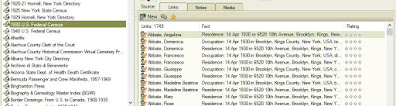

I learned that he was:

- a shoemaker (calzolaio) in his youth

- a dealer or merchant (commerciante) shortly before his first documented trip to America

- a day laborer two years after settling in America, and

- had his "own income" by the time of the 1910 census.

Was Antonio an independent businessman? Are his accomplishments the reason his son Semplicio and my great grandfather Giovanni Sarracino became the owners of apartment buildings and agents for a local brewery?

Was Antonio a wheeler and dealer? What was the source of his "own income"? It may be nothing, but his cause of death was a toxic infection of the kidneys and the heart's inner lining. Were these infections related to the Bronx's underground beer cellars of the time, owned by the breweries with which his son and son-in-law did business?

I've often wondered if my family owned those particular apartment buildings because of their access to the beer cellars. This would make them good partners for the breweries.

The discovery of Antonio Saviano's origin and travels shed a lot of light on him. But now I find I have a ton more questions.

I think it's time for some Bronx brewery history lessons!

And speaking of what documents can tell us: