I have a love/hate relationship with the TV show "Who Do You Think You Are?". I love seeing others experience the joy of finding an important genealogical document. But I hate that every celebrity is the direct descendant of a king or a patriot.

Where does that leave a descendant of peasants like me?

Whether you're the great great grandchild of powerful people or humble railroad workers, you do have an interesting story to tell.

You just have to find it.

Where to Look for Your Story

|

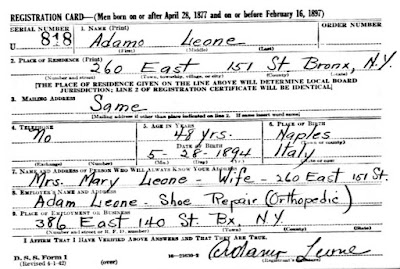

| How could this character NOT be interesting? |

- Did anyone have an unusual job? My great grandfather seemed to go from bartender to apartment building owner overnight.

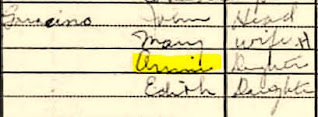

- Did the two sides of your family converge before your parents were married? My two grandfathers lived in neighboring towns in Italy before winding up one block apart in New York City. They could see each other's town from their childhood home.

- Did someone famous come from one of your ancestral hometowns? Hmmm. Well, my dad was in Regis Philbin's high school class at Cardinal Hayes in the Bronx, and George Carlin was expelled from there. But that's more of an anecdote than a story.

- Is someone famous on the same ship as your ancestor or living on their street? I have found unrelated people from my maternal and paternal families on the same ship. That fits better with the "family convergence" idea.

- Do you have an amusing six-degrees-of-separation story? I can connect myself to my favorite movie director, John Huston (1). His daughter Anjelica (2) was in the movie "Daddy Day Care" with Eddie Murphy (3) who was in "Shrek" with Mike Meyers (4) who was in "Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me" with Fred Savage (5) who was in "The Wonder Years" with Josh Saviano (6) who is my third cousin. It's a fun parlor game, anyway.

For me, the story of my entrepreneurial great grandfather Giovanni Sarracino rises to the top of the list.

Where to Start Writing Your Story

One technique for crafting your story is to write out what you know as if it's a movie plot.

- Where are the plot holes, and where should you search for what's missing?

- What was going on at that time in history in the place where your ancestor lived?

- What effect did any historical facts have on your ancestor?

Lots of census forms and directory listings pointed to Giovanni's evolving career path. Using the Fulton History website, I discovered real estate transaction notices in New York newspapers. Giovanni and his brother-in-law Semplicio were working as agents of a local brewery or two. First they were buying and selling buildings for the breweries. Then they were buying buildings for themselves.

Exactly what happened is still a bit of a muddle to me. There is more to learn about these defunct breweries. A visit to the Bronx Historical Society might be what I need.

It's going to take discipline, but you can do it. Put aside some of your research threads for a few days. Find your interesting nugget of a story. Write it down, gather some facts, and see where it takes you.

If you're not a celebrity, you won't be featured in an episode of "Who Do You Think You Are?" or "Finding Your Roots". But you will become an instant celebrity within your family.

You may also enjoy: