You've got your DNA matches. You've got people who share a bunch of your last names. You've probably ID'd a lot of possible relatives.

How will you find your connection to them? How will you connect those dots and figure out if and how you're related?

I've got a handful of these challenges on my plate right now.

|

| Your roots probably spill over to the next town. Don't overlook them! |

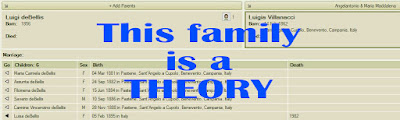

All my ancestors came from a small area in Italy, not much bigger than my home county here in New York. So when someone has a family tree filled with last names I know well, we're probably distant cousins.

Discovering that one marriage from long ago that connects you to your leads will be tough. It'll take a lot of time. You'll need to examine a ton of documents.

That's why you must follow the first rule: Enjoy the search! If you're not pursuing this mystery because it gives you pleasure, you may as well skip it.

To work with my possible relatives, I ask for details at their grandparent and great grandparent level. What names and dates do they have?

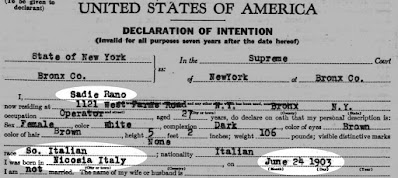

Last year I downloaded every available vital record from my ancestors' four Italian towns. Now I'm branching out. I'm downloading a neighboring town and looking at still another.

With these document collections on my computer, I can try to find birth and marriage records for the names I know. Then I can look for their siblings' births.

I can piece together that family while checking familiar names against my own family tree. If I'm very lucky, I may find a set of marriage documents that includes death records.

In Italy in the 1800s, if a couple married and any of their four parents were dead, that death certificate was included in the marriage records. If either of their fathers was dead and their grandfathers were also dead, the documents include the grandfathers' death certificates. You know what's on their grandfathers' death certificates? Their grandfathers' parents names.

Think about that for a second. A couple's marriage records can give you the names of their great grandparents!

The wider you expand the family of your possible relative, the more likely you are to find a connection. There's a good chance you'll provide them with names and documents they don't have.

Right now I'm searching the documents from that neighboring town because:

- A contact with my great grandmother's last name has roots there.

- My first cousin, whose DNA matches him to BOTH of my parents, has roots there.

- A contact with my first cousin's last name (and ancestors with my maiden name) has roots there and in my grandfather's town.

- One branch of my father's tree has roots there.

There's a good chance I have some relationship to a big chunk of that neighboring town.

And the search does make me happy. I'm connecting myself to thousands of people across the world.

If you enjoy this hobby, cast a wide net. The genealogy community is a friendly, sharing, welcoming network of people. In the end, we've got more in common than meets the eye.