As I looked at my past article about how to use the Italian Ancestry website, one reader comment stood out. She wanted to know why on earth anyone should download all the vital records from their town. Her thought was, "Why spend all that effort when I only need my grandfather's birth record?"

This past week I've been using my downloaded records from one town to add more than 1,300 people to my family tree. In the past, I had only gathered my great grandmother's closest family. Now it's time to connect everyone—as I've done with my two grandfathers' towns.

For at least several hundred years, my ancestors lived in a few rural Southern Italian towns. Being there for so long, there was a lot of intermarrying. As a result, entire towns have a connection through blood or marriage.

The mission of my family tree (current population: 58,553) is to find all the connections.

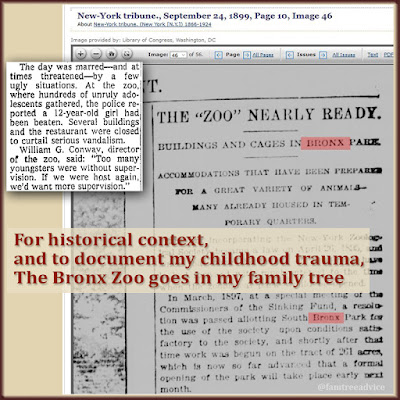

While working on the town of Pesco Sannita (formerly Pescolamazza), I spotted a terrible trend. This is something I would never have known without reviewing *all* the vital records.

|

| Not only is this infant mortality rate horrifying, but the 1st man's 1st wife had 2 stillborn babies before she died at age 29. |

Pesco Sannita had a horrifying infant mortality rate in the first half of the 1800s. It was so shocking that a typical woman was giving birth to 10 babies, and only one or two lived long enough to marry.

The alarming death rate made me realize what a miracle it was for my ancestors to have lived to adulthood.

Here are some examples of what I discovered going through the vital records:

- My 3rd great grandparents, Giuseppe Caruso and Maria Luigia Pennucci, had 7 children between 1829 and 1848. Only 3 lived to marry.

- My 4th great uncle Francesco Saverio Pennucci and his wife Antonia had 8 children between 1824 and 1844. Only 4 made it past infancy.

- Distant relatives Filippo Girardi and Caterina Gentile had 9 children between 1827 and 1844. Only 2 grew up.

- My 5th great aunt Maria Luigia Girardi and her husband had 6 children between 1816 and 1827. Only 1 made it into her 20s before dying.

Because I've studied the neighboring towns, I know this infant mortality rate is unique. My goodness—what was going on in this town at the time? The town's website says Pescolamazza fought for independence from its feudal lord in 1817. The legal proceedings dragged into into the 1850s.

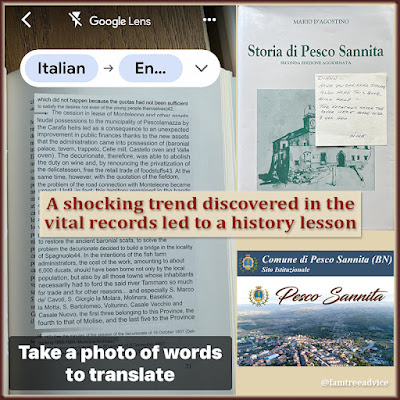

There is one definitive book on the subject that isn't online. It's called "Storia di [History of] Pesco Sannita" by Mario d'Agostino. Suddenly I remembered that a distant cousin gave me a book about the town years ago. When I found it on my bookshelf, I saw it is the very book I couldn't find online! And it mentions a lot of names that I can tie to vital records. I started translating the book years ago, but I didn't get far. Uh oh. Another genealogy project for me.

|

| A much appreciated genealogy gift from a cousin I met online is helping me understand the sad, deadly history of my great grandmother's town. |

I used the Google Translate app on my phone for a quick-and-dirty translation of a few pages. It seems as if the town became isolated once they severed ties to their feudal lord. They were unable to take their goods to market. They had a real problem to overcome.

They needed to build a new bridge, at great cost to many, including the townspeople. By today's standards, it took an eternity to build that bridge and restore financial security to the townspeople. This happened in about 1861.

The mortality rate was much better in the second half of the 1800s. In an 1892 newspaper advertisement, the town is looking to hire a doctor. The ad ran several times in the Corriere Sanitario—the Healthcare Courier—way up north in Milano. I suspect the high infant mortality rate was due to poverty, malnutrition, and a lack of medical care.

Visiting Southern Italy today, it's hard to imagine the extreme poverty and lack of opportunity our ancestors faced. All we see is the sublime landscape and ancient architecture.

It took a deep dive into the town's vital records to realize the daily threat to my ancestors' lives. The next time you wonder why I'm piecing together my ancestral towns, remember that's what it took to notice a deadly pattern.

And speaking of piecing towns together:

![I get angry when my seat on an airplane is too cramped. My poor ancestors rode in the belly of one of these. I get angry when my seat on an airplane is too cramped. My poor ancestors rode in the belly of one of these. ... Ancestry.com. New York Port, Ship Images, 1851-1891 [database online]. Provo, Utah: MyFamily.com, Inc., 2004. Original data: Ship images obtained from and reproduced courtesy of Mystic Seaport.](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjrXM3ChMWg4WfEZpcqoi05bTQd5lSKLcseicXO345jpmMZtVS31qAIUhNTbnAtbVVq9dklCiSuDbwH3L1pBupNXfJikq8kpIdxw71_KKUd_7g0solx2WMTs8j28SLvIfNGzku04s_40Eg/w400-h301/073019-ship.jpg)