I dream about transcribing old Italian vital records. That's how much I love it. In fact, I don't enjoy U.S. censuses anymore. I'd much rather be working with my old Italians.

But a new project has come up. My son's girlfriend (let's call her V) lost her father. My son told her I'd want to do her family tree for her since she didn't know her ethnic background. V said she would like that.

I began with facts from her father's obituary. I had his parents' full names and his wife's maiden name.

I found V's grandparents right away. I discovered they had been in the same Pennsylvania county for many generations. This is the same county where V grew up. The same county where I raised my kids. The same county where V and my son live today.

Then I tapped into a few local histories that featured V's last name. In one document from the county's historical society, I found generations of V's family. As I dug into it, entering names into V's family tree, I found exactly what I was looking for. Her paternal immigrant ancestor!

Her 9th great grandfather (NINTH!) had come to America from France in 1715. He was a French Huguenot who joined the Quaker religion that was so common in his new homeland.

Let's step back a second. In my first session, I climbed all the way up to V's 9th great grandparents born in the late 1600s.

Did I feel joy about this rapid success? No. I mean, I was happy to find the unexpected source of V's Italian-sounding last name. But I was a little angry that it was all so easy to find.

I know the names of five of my 9th great grandparents. They came after years of research, and the help of an Italian historian from my Grandpa's hometown. But after very little time, I know the names of eight of V's 9th great grandparents.

What I really felt was jealousy. Is this how easy it can be for white people with deep, deep roots in America? My direct ancestors came to America between 1899 and 1920. That missing 1890 census never bothered me because my people weren't here yet! With V's family tree, I'm seeing for myself how far back you can go with records on Ancestry.com. For the first time, I'm looking at the early censuses with no names, just tick marks.

My first day working on her tree, I racked up ancestors so fast my head was spinning. I had to stop myself from going further.

|

| Make sure all your family tree work reflects your best genealogy practices. |

Why stop? Because I want to give V a family tree that shows all I've learned. I started this blog to encourage us all to be more professional with our genealogy research.

I've spent years developing a strict and thorough genealogy discipline. I want to give V the benefit of all I've learned. I want us all to apply the same discipline to someone else's family tree as we do to our own.

That's why I went back to the beginning. In this case, the beginning is the documentation I found for her grandparents.

- I downloaded each genealogy document as I found it.

- I gave it a logical file name and added pertinent facts to its file properties.

- I placed the image in Family Tree Maker and added the date of the document.

- I assigned it to a media category.

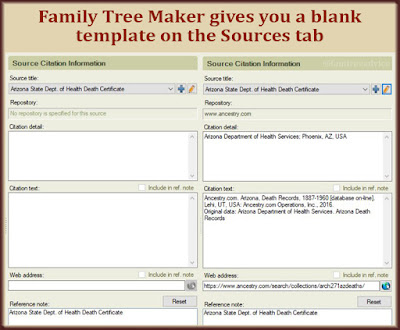

- I entered facts from the document into the tree and created the source citation.

- I shared the document, facts, and source citation with everyone mentioned in the document.

- I verified addresses from the documents by finding them on Google Maps.

In short, I used all my family tree-building discipline on someone else's family tree.

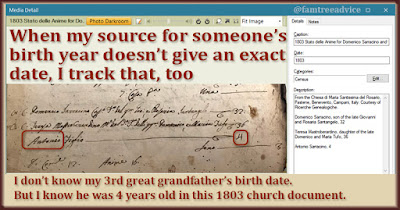

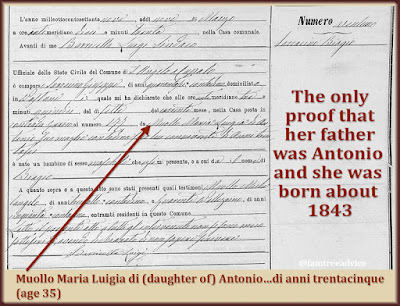

I love helping people find their ancestors among the Italian vital records. I treat their documents and family trees with as much discipline as I do my own. When I send them a batch of files, I want each jpg's file properties to include a file name and where the image came from.

It makes perfect sense to keep up your genealogy discipline for every family tree you work on. You're creating something for the ages. You're going to want people to pass it down—and rely on it. That's why you must take the extra steps to produce high-quality work every time.

As I said, I felt anger and jealousy over how easily V's family tree is coming together. But those aren't the only emotions I felt.

I felt gratitude when the genealogy community on Twitter solved a problem for me. One of V's great grandparents was an immigrant. On one census he said he was Austrian. On two other censuses he said he was German. But his World War II draft registration card said he was born in "Kofedesh" Hungary. So now he's Hungarian? I wanted to see Kofedesh on the map, but it didn't exist. At least, not with that spelling.

I put out the call to Twitter. Does anyone know what town sounds like Kofedesh? To my delight, @sosonkyrie found it almost immediately. He sent me a Wikipedia link about Kohlfidisch, Austria, that included a spoken pronunciation. What does Kohlfidisch sound like? Kofedesh!

As for the shifting nationality of V's great grandfather, that isn't surprising. His town was in Hungary when he registered for the WWII draft. It's in Austria now. And V's great grandfather was part of its German-speaking population. (Where are you from? It depends on the year.)

I feel one more emotion as I work on V's family tree. Guilt. I do some genealogy work every single day. I'm always advancing my project to document all the relationships in my ancestral hometowns. Now I feel guilty about not working on my own family tree.

Sometimes it feels as if I'm doing something wrong. Something bad. I'm ignoring my family tree. When those feelings take over, I take a "break" by working on my Italian vital records database. When U.S. census after U.S. census for V's family got to be too tedious, I went to my happy place. I renamed more downloaded Italian vital records to make them searchable.

I know my genealogy discipline will produce a robust family tree for V. And if she ever winds up creating my grandchild, guess who will inherit my work?

Keep the future in mind as you work on any family tree. Stay true to your strong genealogy discipline knowing it will always pay off.