This is the third in a series of articles to help you understand Italian vital records without speaking Italian. If you missed the other two, please check out:

- Simple Tips for Understanding Italian Birth Records

- Simple Tips for Understanding Italian Death Records

As you try to go back another generation in your family tree, marriage records can be crucial. How can you find your great grandfather's birth record if you don't know his parents' names?

When your ancestors married in Italy, they had to provide a copy of their birth record. That means you can have a good deal of confidence in the age recorded on the marriage record. If their parents weren't alive to consent to the marriage, they had to provide death records. And guess what? If their late father's father was dead, they had to provide his death record, too.

Depending on the year, and what's available online, you may see:

- copies of these records (jackpot!)

- the birth and death dates written on the marriage record (a good runner-up)

- a list of the documents produced (disappointing).

If your ancestors' Italian marriage records are online, there are 3 types to see:

- Matrimoni—The actual marriage record. It may include:

- the civil marriage date

- the church marriage date (yes, they can be different)

- the 1st, and possibly 2nd marriage banns, when the couple posted their intention to marry.

- Matrimoni Pubblicazioni—A record of the couple posting their intention to marry. It's like today's "speak now or forever hold your peace."

- Matrimoni Processetti/Allegati—This is the goldmine. This can include the couple's birth records and any parents/grandfathers' death records.

|

| When available, this set of Italian marriage documents is a positively priceless addition to your family tree. |

Be sure to search for all 3 types of records on the Italian Antenati website or FamilySearch.org.

Let's look at examples of these documents and how to find the genealogy facts you need. I chose an 1831 marriage from my maternal grandfather's hometown, Baselice in Benevento.

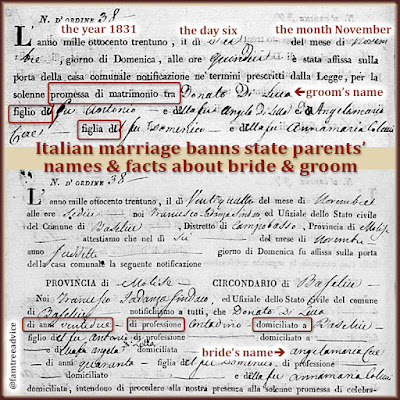

The 1st banns are very brief, but you will learn the names of the bride and groom's parents. Here is the format:

- The date of the document, written in longhand. You must memorize the Italian numbers or keep your link to FamilySearch's Italian Genealogical Word List handy.

- Look for the words "promessa di matrimonio tra." This means promise of marriage between, so we can expect to see the couple's names. Remember that in Italian documents the male is always listed before the female.

- Look for the groom's name followed by his father's and mother's names. Then find the bride's name followed by her father's and mother's names.

|

| Top, the simpler 1st marriage banns. Bottom, the more detailed 2nd marriage banns, filled with facts for your family tree. |

The 2nd banns have the same information plus more details about ages and occupations. In this example we have:

- The date of the document and the name of the town.

- The groom's name and age ("di anni ventidue" = age 22), where he lives ("domiciliato a" = living in)

- His parents' names, his father's occupation, and where they live. In this case, the word "fu" before each name tells us the groom's parents are both dead. So we see their names and nothing else.

- The bride's name and age ("di anni quaranta" = age 40; there's a big age difference in this couple).

- Her parents' names (both are dead), and a blank occupation and home for her deceased father.

- Below the town official's signature it says this completes the process. Without opposition, the couple may marry.

I like to record the date of both marriage banns in my family tree software.

Next is the marriage record, which may contain 3 different dates. In the example shown here, there's a wide column and a narrow column. The narrow column is a statement from the local parish that tells us when a priest married the couple.

Don't let the format fool you. It begins with one date, but that's the date someone wrote this note. A little further down is another date. That's the marriage date. This one says:

"…la celebrazione del matrimonio é seguita nel giorno dieci del mese di Dicembre anno suddetto"

That translates to:

the celebration of the wedding took place on the 10th day of the month of December the aforementioned year

This is the marriage date I will record in my family tree. This document mentions the specific church name (San Leonardo Abate). I'll enter the full street address of this church—which I visited in 2018.

|

| You don't need to understand everything on an Italian marriage record. Find these keywords and you'll see the info you want for your family tree. |

In the wide column of the page we see another date, which may be a few days earlier than the church date. On this date, the town official:

- saw the couple in the town hall

- determined there were no impediments to their marriage

- pronounced them legally married.

It's an odd concept for us to relate to, having a civil ceremony and then a church ceremony. I've chosen to put my own spin on the dates. I record the earlier date in my family tree as the marriage license. I don't know how it was for 19th century Italians in a Church-centered society. Did they wait for the church marriage before they lived together?

The format of the wide column of this marriage record is as follows:

- The date the couple appeared in town hall to be married.

- Find the word "comparsi" (appeared). After that is the groom's name (Donato diLuca), age ("di anni ventidue" = age 22), place of birth ("nato in" = born in).

- Next is the groom's father (and potentially his occupation and where he lives) and his mother (and potentially where she lives).

- Then we see the same information for the bride. We may not see her occupation, but sometimes we do. This bride's parents are both dead, but there's an extra bit of very important information. It says "vedova di Leonardo Cocca." Bride Angelamaria Cece, who is 18 years older than the groom, is the widow of Leonardo Cocca ("vedovo/a" = widow). If you find the matrimoni processetti, you should see the late spouse's death record.

- The next handwritten date you see is the date of the 1st marriage banns.

- The long handwritten section is a list of the documents that the couple had to provide:

- the groom's birth record

- the groom's parents' death records and his paternal grandfather's death record

- the bride's birth record

- the bride's parents' death records and her paternal grandfather's death record

- the bride's 1st husband's death record

- their marriage banns with no impediments to their marriage

- The final section includes that names, ages, and occupations of 4 male witnesses. Many times you'll see only 2 witnesses. Take a look at the names to see if there is a stated relationship to the married couple. You may find that a witness is a "cugino" (cousin), "zio" (uncle), or "avo" (grandfather).

The marriage facts you need for your family tree are not hard to find. Even if the town runs out of marriage forms late in the year and has to hand write the whole thing, don't worry. You can find those keywords and see what follows. With practice, you can memorize number and month words, and the important keywords.

You'll focus in and find what you need:

- the handwritten date, fully spelling out the year, day, and month

- comparsi, alerting you to the name of the groom

- di anni—the next number is their age

- professione, which is obviously profession

- domiciliato, which looks like the word domiciled, or living in

- nato, telling you where they were born

- figlio/a di, meaning son/daughter of, which leads into the parents' names

- vedovo/a di, which, if you see it, tells you one of the two has been married before

There's no reason on earth for you to see a big block of foreign words and call for help. You know exactly which words to look for. You know what you'll find right after those words. Any words you can't make out are probably on FamilySearch's Italian Genealogical Word List.

With a bit of practice, you'll see the pattern to the documents. You'll recognize the keywords—even when the handwriting is the worst. Are your ancestral hometown's documents available online? Then nothing should stop you from using these images to build your Italian family tree.