|

| Why not share your photos on Find-a-Grave? |

You may not have time to transcribe genealogy documents as a volunteer. And goodness knows there are a lot of opportunities to help out in that way.*

But what if the genealogy research you're doing for yourself can help people you don't even know? Wouldn't it thrill you if someone else shared research work that's invaluable to you?

Last month I took a deeply satisfying genealogy vacation to Italy. I visited each of my 4 ancestral towns in the province of Benevento. I visited each town's cemetery and took lots of photos. I concentrated on last names that meant something to me, but then I'd find 30 graves with that last name.

Now I'm going to share those photos on the Find-a-Grave website.

First I clicked the Cemetery tab on the website to browse for cemeteries in Italy. There were no listings for my 4 cemeteries, so I'm creating them.

To prepare for my vacation, I saved the longitude and latitude of each cemetery in Google Maps. Now I can use those numbers to precisely locate my 4 cemeteries on the Find-a-Grave map.

|

| I took a photo of the cemetery entrance just so I could add it to Find-a-Grave.com. |

Once I create the new cemetery, I can upload a photo of its entrance. You see, before my trip I read someone's tip to be sure to take a photo of the cemetery entrance. So I did.

Next, I can drag and drop all my photos from that cemetery at once. After dropping the photos, I simply go down the list adding the deceased's name as the caption.

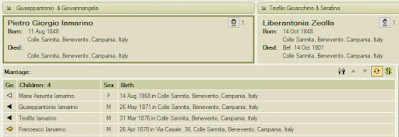

If you know the person whose grave you're uploading, it's nice to add a memorial. A while back I added a photo of my great great grandmother's grave in the Bronx, New York. I also wrote a paragraph outlining what I knew about her. Today my research on her family has gone much further, so I updated my memorial.

|

| I created, then updated, the memorial for my great great grandmother. |

I have so many photos to upload, and then I will detail each one with the dates I see on the grave. Someday, I hope relatives of the deceased will contact me. Maybe we'll be cousins!

What can you do to preserve your family history and, at the same time, pay it forward?

* Volunteer Opportunities:

- Indexing record images at FamilySearch.org

- Fulfilling photo requests at Find-a-Grave

- Taking photos or transcribing for Billion Graves

- Transcribing images for the Italian Genealogical Group