You know that guardedly ecstatic feeling when you think you're looking at the answer to your biggest family tree mystery?

Should you shout EUREKA! or keep reading the document you've found to make sure you've got it right?

This happened to me a few times today, and I was giggling with joy!

|

| I had his death photo. Now I have his birth and marriage records! |

Recently, I filled out my chart of direct ancestors, color-coding the names to correspond to each of my four grandparents. That's when I realized I hadn't gotten further than my third great grandparents on my maternal grandmother's branch. And those names were from an unreliable source.

I needed to find Italian documents for my grandmother's grandparents: Antonio Saviano and Colomba Consolazio. Only then could I be sure of their parents' names. And maybe I'd learn their grandparents' names.

My great great grandfather Antonio Saviano presented me with another problem besides his ancestors' names. I didn't know where he was born, and he seemed to move a few times before coming to America. I haven't found any other Italian family in my tree that moved more than once in 1800s Italy.

The Saviano and Consolazio origins were my only brick wall.

First I found Antonio and most of his family on an 1898 ship manifest coming to New York. They stated they were from Sant'Angelo a Cupolo. That's a little town in the province of Benevento. But I'd always heard they were from Avellino.

Next I found the World War II draft registration card for Antonio and Colomba's son, Semplicio Saviano. It said he was born in Tufo, Avellino, Italy. Great! Now I was onto something.

Then I ordered microfilm of Tufo vital records to view at my nearest Family History Center. I found that Antonio Saviano and Colomba Consolazio had a son before Semplicio named Raffaele.

I looked in the Tufo microfilms for Antonio and Colomba's births and marriage. But they weren't there!

Thanks to Colomba's brother's marriage records, I discovered that the Consolazio family came from the neighboring town of Santa Paolina.

So, with only days left to order microfilm, I ordered four reels from Santa Paolina, Avellino, Italy. Today I went to see them.

I immediately set out to find Antonio Saviano's 1843 birth record. It wasn't there, and I was disappointed. but I continued looking.

And then it happened.

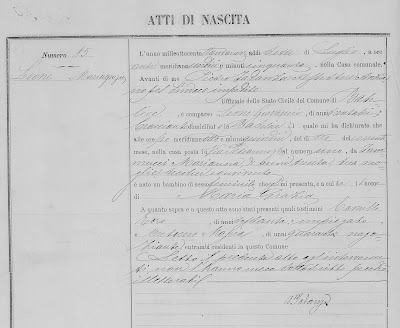

I wasn't sure at first, so I kept quiet. But there I was, looking at Colomba Consolazio's birth record. My great great grandmother was not born on the date I saw on her death record. She was born three years earlier, and her name was Vittoria Colomba Consolazio.

There was an extra paragraph in the center of the birth record. It stated that Vittoria Colomba Consolazio married Antonio Luigi Saviano on 1 June 1871 in Santa Paolina!

I rewound that reel of film faster than I thought possible. I had to get to the 1871 marriage records ASAP.

|

| And the bricks came tumbling down. |

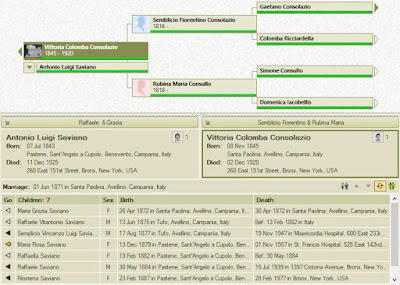

When I found the marriage banns and marriage record, I had an answer I never expected. Antonio Luigi Saviano was born on 7 July 1843 in Pastene.

Pastene is a small section of Sant'Angelo a Cupolo in Benevento! That's where the family was living before they came to America. That's where my great grandmother and her younger siblings were born.

So Antonio was born in Pastene, moved to Santa Paolina to marry Vittoria Colomba, had one baby who died at four days of age, moved to Tufo to have two more children, and moved back to Pastene to complete his family.

I learned Antonio's parents' names were not what I saw on his death certificate. They were Raffaele Saviano and Grazia Ucci. Grazia died before 1871. I learned Antonio's birth date and his town of birth.

I learned Vittoria Colomba's real name, real birth date, and her parents' full names. These facts were almost entirely wrong on her death certificate. Her father was Sembricio Fiorentino Consolazio, son of Gaetano who was the son of Saverio. Sembricio's mother was Colomba Ricciardella.

Finally, I learned about Vittoria Colomba's mother. On her death record, her mother was Rafina Zinzaro. In the Tufo documents, she was Rufina Zullo.

But on an 1818 birth record I discovered Rafina Zinzaro / Rufina Zullo was born Rubina Maria Consullo (sometimes written as Conzullo). Her parents were Simone Consullo and Domenica Iacobellis.

During my visit today I jotted down the facts for every Consolazio I could find, and I will go back to finish that work. Suddenly my family is much bigger thanks to the Consolazio ancestors that had been hiding behind that brick wall.

Now it's time to scour the Pastene and Sant'Angelo a Cupolo records I downloaded to get the facts on every Saviano and Ucci.

Can I shout EUREKA now? EUREKA!!!!