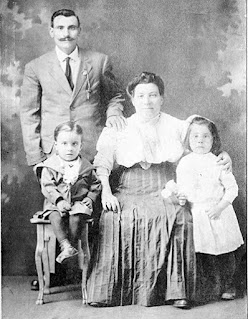

I've spent 90% of my genealogy research time alone. Most of us relish being left alone to sort through the facts and documentation for people in our family tree.

The other 10% of my time used to consist of:

- a couple of genealogy conferences

- emailing relatives and potential relatives

- watching Ancestry's Crista Cowan present extremely helpful lessons on YouTube.

That all changed this year.

I still want plenty of alone-time to dig into the research. But throughout the day, I check in with an extended community of genealogy researchers online.

|

| You'll find a welcoming, generously helpful genealogy community online. |

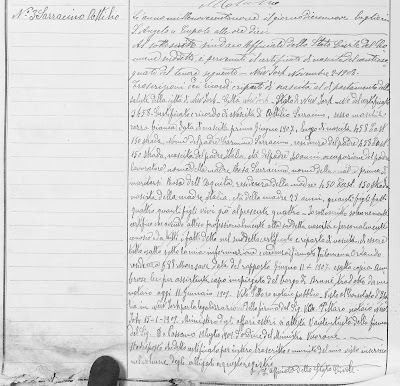

- Get help translating documents from another language.

- Get opinions on how to read a poorly written name on an old document.

- Get advice on where to search for missing information.

- Be the first to know about a new family history resource.

You'll quickly see who the experts are within any group. If you send them a friend request on Facebook or follow them on Twitter, you can stay on top of their latest advice.

I spent years transcribing facts from Italian birth and marriage records. Then an expert in a Facebook genealogy group showed me that I was reading baptism and marriage dates incorrectly!

In a LinkedIn genealogy group, I learned about a website with thousands of Italian vital records. In a Facebook genealogy group, I learned about free software to make it easy to download those records. Twitter helps me stay on top of genealogy tips and upcoming conferences or seminars.

Here are some of the top platforms for interacting with fellow genealogists:

Facebook

Click the Groups icon on your Facebook homepage and start typing in search terms. Search for "genealogy" or a specific type of genealogy, like "Irish genealogy". Many groups have an administrator who must OK your request to join. Once you're in, read the group's rules of conduct. It's usually the first post on the page.

Twitter

When I first joined, I would search for #genealogy or #familyhistory to see what was happening. Now my Twitter feed is 99% genealogy-related. Why? Because all I do is:

- interact with genealogy posts

- follow other genealogists

- post about genealogy.

Google+

Search for genealogy on the homepage. You can choose from Posts, Communities, Collections, or People & Pages. I haven't done much exploring yet, but I do maintain a genealogy collection where I post each of my blog articles. (Note: This doesn't exist anymore.)

You may also want to look at Instagram, Pinterest, and LinkedIn. Search for genealogy topics. Follow the experts you've found on other social networks.

You'll find your fellow genealogists are willing to help, collaborate, and inspire you.

I hope to see you in my Facebook groups: Fortify Your Family Tree and My Italian Family Tree.