Ten years ago I needed to take control of my family tree digital files. I had a growing collection of census forms, draft registration cards, vital records, and more.

I'd already settled on my preferred way of saving these files:

- A folder for each type of document

- A naming convention that groups a person's documents together:

- LastnameFirstnameYear for a census or ship manifest (I use the head of household's name for a census.)

- LastnameFirstnameBirthYear for a birth record

- LastnameFirstnameWW1 for a draft registration card, etc.

But my well-named image files, sitting in all those different folders, didn't show me the big picture.

How could I see at a glance every document I have for a particular ancestor? And how could I quickly see which documents are missing?

Use the Technology You Know

That's when I turned to my old pal, Microsoft Excel.

For years I'd been using Excel spreadsheets on the job. I tracked progress on large-scale projects. I built formulas to show an accurate cross-section of the content on a website I manage. I kept tabs on my freelance hours for invoicing.

Why wouldn't I use Excel to create a genealogy research inventory?

My genealogy "document tracker" has 1540 lines right now. I have one person on each line. There are columns for each type of document I collect. The last column gives me space to note what's missing.

For example, for one of my grandmother's cousins, the "To find" column contains this:

- 1915 census

- 1920 census

- 1925 census

One Spreadsheet Tells the Whole Research Story

Now it's time to get even more value out of my document tracker.

I've been looking at sample research logs on different genealogy sites. A research log is a disciplined way for you to note:

- What you're searching for (the 1930 census, a WWII draft registration card, etc.)

- Where you searched (National Archives, State Library, Ancestry.com, etc.)

- How you searched (by first name only, browsing through the whole census district, etc.)

- Your thoughts on what to try next

The research logs I found were much more complicated than I wanted. For starters, I'm satisfied with the list above.

So I've added a second sheet to my document tracker Excel file and named it Research Notes. The first column is for the person's name. I added four more columns to match the four items in my list.

How to Start Using Your Research Notes

The next time I'm trying to find a specific document—like the elusive 1940 census for the Raffaele Saviano family—I'll add a line to the new Research Notes worksheet.

I might note that I tried searching for the family using only their first names. And that I used Americanized versions of their Italian names. I'll add that I tried this on Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org.

When I'm ready to call it quits for the moment, I'll add a note about what I think I should try next.

Finally—and this is a cool Excel trick—I'll add a link from this research note to Raffaele Saviano's line on the first worksheet where all of his documents are listed. And I'll add a link from there back to his line on the new Research Notes worksheet.

My favorite thing about linking between the sheets is this: You can reorganize the lines on either worksheet and not break the links. You can sort them, add new lines in the middle, do whatever you need to do, and the links will still work.

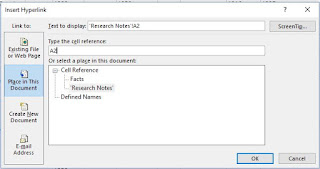

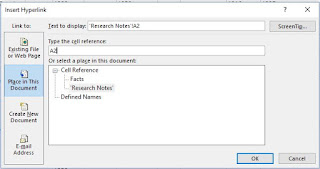

Here's how to create a link between the two worksheets in a single Excel spreadsheet file:

- Make a mental note of which line number holds your ancestor on your new Research Notes worksheet. For example, I have Raffaele Saviano on line 2.

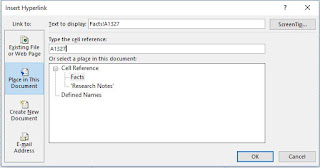

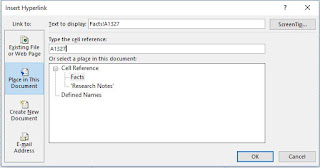

- Click the empty cell where you want to add the link. You'll want to devote a column to these links. In my example, I'll go to Raffaele Saviano's line (1327) on my Facts worksheet and click in the empty "Link to Notes" column.

- On the Insert toolbar or ribbon, click Link and choose Insert Link.

- Click to select the name of your new research notes worksheet.

- In the field labelled "Type the cell reference" it may say "A1" by default. Change it to A2, or A and whichever line number you need to link to.

- Click OK and you'll see your link.

Now make a mental note of the line number for this ancestor on the Facts worksheet. Go to the Research Notes worksheet and link back in the same way.

Click the links to see them work.

Now you can have all of these facts at your fingertips. It's 100% searchable, sortable, and update-able. Download a sample spreadsheet to build on.

My favorite thing about Excel: I know it can do a million more things I haven't even thought of yet.

For more detail on the document tracker, see: