No rubber gloves necessary. Family tree housekeeping uses no rags, cleansers or mops.

I don't enjoy cleaning my house. The dog's gonna mess it up in no time anyway. But I will make time for family tree housekeeping. Unlike my house, my beautifully polished family tree will stay pristine forever. Don't you want your family tree to be your legacy? Can you imagine the joy of the relative who inherits your amazing family history research?

Most of us jump into this genealogy hobby all excited, grabbing names and documents left and right. We learn more and get more professional about it as we go. But there's a good chance our earlier work doesn't live up to our current standards.

Here are 3 important family tree housekeeping tasks you can do while you're watching something boring on TV.

1. Add breadcrumbs and links to your documents

Your family tree should have lots of images of:

- census sheets

- ship manifests

- draft registration cards

- vital records

|

| Add facts to each document in your family tree. |

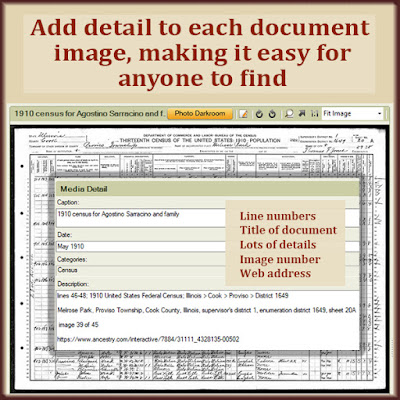

But you need to go back to those older document images. Add enough facts to allow anyone to retrace your steps and prove you're right.

I like to add:

- the line numbers containing your people

- the name of the document database

- the image number if it's one of many

- the web address (URL)

2. Upgrade your sources

How many times have you kicked yourself for not writing down where you found a particular fact?

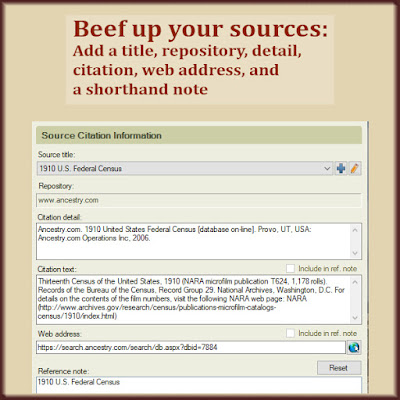

Make a habit of creating good, reliable sources each time you add a new type of image to your family tree. All the unsourced facts and images in your tree need your attention.

When you find a fact online or in a reference book, look for a description of the document collection. You can copy the citation detail and citation text for the collection from its source. That may be a page on Ancestry.com, FamilySearch.org, or in a book.

|

| Add enough facts to your source to make it official and retraceable. |

There's no need to go overboard. I don't have a separate source for each document or fact, because I would have more than 3,000 sources. I have one source for the 1910 U.S. Federal Census, for example. The source includes the URL to the collection, a description and citation. Each 1910 census image includes the URL to that specific page. And each fact taken from a 1910 Census links to the one source.

3. Standardize your place names

My parents lived a block apart as kids. So my early family tree research focused on their Bronx, New York, neighborhood. Nearly every family lived on numbered streets, with very similar addresses. After a while I realized I needed some consistency. I decided to spell everything out with no abbreviations:

- 221 East 151st Street, Bronx, New York, USA

- 237 East 149th Street, Bronx, New York, USA

- 615 West 131st Street, Bronx, New York, USA

I love it when I start to type an address, and the suggestion shows I've got another relative living there.

|

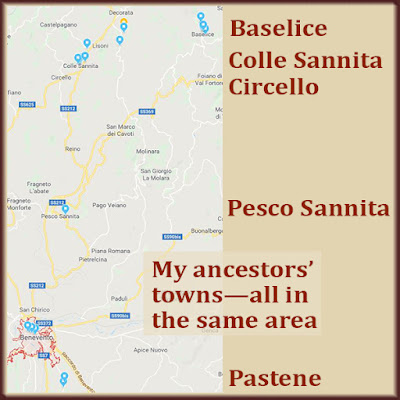

| This orderly arrangement of addresses makes it easy to see which relatives lived near one another. |

I also like to use my software's ability to locate each address on a map. Every address is neatly arranged. I can drill down by country, state or region, county or province, town and address. For each address, I can see the list of people I've associated with the address.

If your tree has only a few thousand people, you might tackle these housekeeping tasks in a weekend. If you've gone wild and have 19,000 people like I do, it's more of a challenge. But set aside time now and then. Chip away at it. You can get this done.

In the end, you'll have a high-quality tree that will show genealogy newcomers how it's supposed to be done.