NOTE: There is a way to make your sources indisputable. Please see "Taming a Tangle of Source Citations."

Don't practice smash-and-grab genealogy. Make this method an unbreakable habit.

Seventeen years ago. That's when I graduated from scribbling in a notebook to building a family tree on my computer. I've had Family Tree Maker and an Ancestry.com subscription since 2002.

From the start, I never liked the option of saving a fact or a document to my family tree on Ancestry.com. I hated the ridiculously long source citations it added to my tree. I wanted my sources to be clear and easy to understand.

Because I run a tight ship, I have 275 sources in my Family Tree Maker file. And I have 20,963 people at the moment.

Here's how I keep my sources neat but thorough and retraceable.

|

| Once I found the citation detail and citation text on Ancestry.com, it became too easy. I had to do it. |

One Name to Rule Them All

When I started building my family tree, most of my sources were census pages and ship manifests. I didn't know what other people were doing. I only knew I wanted clarity. So my census source titles are as simple as can be:

- 1900 U.S. Federal Census

- 1910 U.S. Federal Census

- 1920 U.S. Federal Census

- 1930 U.S. Federal Census

- 1940 U.S. Federal Census

If my tree has that the source of a person's address as the "1930 U.S. Federal Census," there's no mistaking where it came from. It doesn't need to say, "United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1930. T626, 2,667 rolls."

But a simple source title does not give us everything we need in our family tree. Behind the scenes, we need all the information. We need an absolute way to get back to the source. We need a link to the proof of each fact in our tree.

|

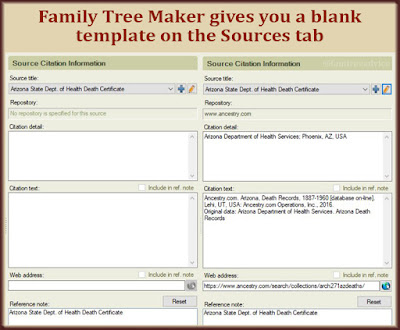

| Fill in these details for the main source, not for each fact or document. |

More Details Under the Hood

Family Tree Maker has a Sources tab where you can see and control all your sources. I've gone down the list of source titles looking for a few things:

- Are people attached to this source? If not, I can delete the source. Maybe it belonged to people I've removed from my family tree.

- Are there duplicate or very similar titles? If I decide to merge a couple of sources, I have to update each person with a fact linked to the source I want to merge.

- Does each source have a clear title, citation details, a web address, and a repository?

If a source needs more detail, I go look it up. For example, I'll look up the 1915 New York State Census on whichever website I prefer. It can be Ancestry.com, FamilySearch.org, or any of the other official sites you may use. (Yes, it may be in a book, too.)

Instead of going to a particular document or record, go to the top-level page for that collection. On Ancestry.com, that page has the source citation detail and text, the exact name of the collection, and its URL.

These extra details make your family tree research more reliable.

|

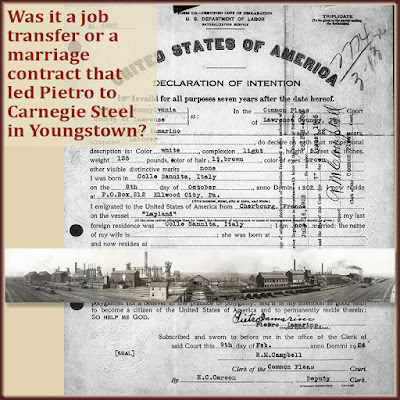

| Add enough details to each image to allow anyone to find it for themselves. |

Specific Micro-Details Where They Count

I want each document image in my tree to show exactly where it came from. It should tell anyone who's looking at it how they can find the original.

On the image of a 1920 ship manifest, for example, I added a breadcrumb trail to the description.

If you view this immigration fact in my tree, you'll see only the source title: "New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957". But the image itself has a description. And that gives you everything you need to know to find the original image file:

- Line number(s). For a ship manifest or census form, I note which line number(s) to look at.

- Source title. This is the exact name of the collection as seen on Ancestry, FamilySearch, or wherever. This will match my source title mentioned above.

- Location of the film. Most of our genealogy documents exist on a roll of film somewhere. If I were trying to find that roll of film in a drawer at an archive, where would I look? This is always shown beneath the source title on Ancestry. For example, Roll > T715, 1897-1957 > 2001-3000 > Roll 2853. Or Wisconsin > Milwaukee City > 14 > Draft Card S.

- Image number. If I asked you to go to John Stefaniak on a roll of Milwaukee, Wisconsin draft registration cards, it'd still take you a while to find him. So I include the image number. For example, image 664 of 973.

- Web address. Sure, a URL may be different today than it was 5 years ago. But maybe it won't change for decades. And if it does, the film location and image number are even more important.

If you haven't been capturing these details for your documents, you may feel overwhelmed. Don't feel that way. Make it a habit going forward. Add a chunk of this annotation work to your annual genealogy goals. I finished all 630 of my census documents, but I have to go back and fix many of my 365 ship manifests.

The name of the game when it comes to your family tree's sources is usefulness. Each source should be useful in these 3 ways:

- Understandable. Anyone can see where your information came from in general.

- Retraceable. Anyone can follow your breadcrumbs to get to the original document collection.

- Specific. At the document image level, anyone should be able to see exactly where this one unique image came from.

Make this a mandatory part of your fact gathering from now on. Don't just get the image and put it in your family tree. Don't just add the facts and let the image serve as your source. Gather all the facts about your source and record them where they belong. Right away.

Doing it right, from the start, makes the whole process much easier.