I've always done my family tree building in desktop software (Family Tree Maker). Then I synchronize it with my Ancestry family tree. I don't have "hints" turned on in my desktop software.

I didn't see much value to hints. They were usually wrong for my family. I never looked at them again.

Recently, I've been collaborating on several family trees, working directly on Ancestry. As a time-saver, I tested out the hints for these trees. I have no doubt that the technology behind Ancestry's hints has improved.

If you keep a few things firmly in mind, these hints can be a terrific benefit to your research. Very basically:

- Don't accept every hint you see.

- Don't believe someone else's unsourced family tree without investigation.

- Think of hints as a little voice in your head saying, "Maybe this is the answer."

That little voice can save you time and steer you in the right direction. But you still have to proceed with caution.

Before I continue with the best ways to use family tree hints, a quick word about unsourced family trees. My own 42,800-person family tree serves up tons of hints to people of Southern Italian descent. But much of my work is missing sources. What's my excuse? I'm working to connect everyone who lived in my ancestral hometowns. If I added the images and sources as I went, I might not live long enough to complete my project! I'm building this tree as a database, and eventually I will add more and more images and sources.

The family trees you see as hints may have facts without sources, too. Don't dismiss them right away! Those trees may represent a family's oral history. Or the builder may be doing what I'm doing—gathering facts from published vital records. Take these hints as what they are: HINTS.

Now let's look at the 3 ways to best use family tree hints.

1. Locate Many Documents at Once

Hints in themselves are a powerful search tool. Instead of sifting through all the search results for a person, you can see the best results in one step.

|

| I finally see the value in Ancestry hints. Here's how to use them without getting into trouble. |

As an example, let's look at my step-grandmother, Sadie. When I view her profile in my Ancestry family tree, I see 3 hints (you may see many more):

- Sadie in 3 other family trees

- Sadie's naturalization papers, complete with her photo

- Sadie's Social Security Death Index listing

Since I do the work myself, I already have Sadie's naturalization and SSDI. These 2 results are a quick way to add solid facts to your tree without the effort.

Don't accept the Ancestry member trees hint without giving it a lot of consideration. More on that next.

2. Find People From the Same Family

When you do look at the Ancestry member trees hint, there are a few things to consider:

- If they have different information than you, what is their source? Do they have something right that you have wrong?

- Why is your person in their family tree? Are they a relative?

- In my 1st of 3 tree results, I've stumbled upon the great grand-nephew of my step-grandmother. I don't have much info on Sadie's nephew, so this is a way to see who his descendants are.

- In my 2nd tree result, someone has pulled most of my family into his tree. When I went to send him a message asking why, I found that we'd already had a conversation about this long ago. We do have an extremely distant connection.

- My 3rd tree result belongs to my friend and collaborator. Her husband is the nephew of my great aunt.

|

| A family tree can be a valid hint, but don't accept it. Think of it as your homework assignment. |

It's not uncommon for me to find family trees that have pulled facts and documents from my tree. I can look at these trees to find my connection to their family, and maybe discover a new branch. But these are not hints to simply accept and add to your tree.

Instead, explore each hinted tree to see what they've done. Then do the research yourself. For example, I will not pull in my step-grandmother's nephew's family. But I will use that tree as a suggestion to search for more documents on Sadie's nephew and his family.

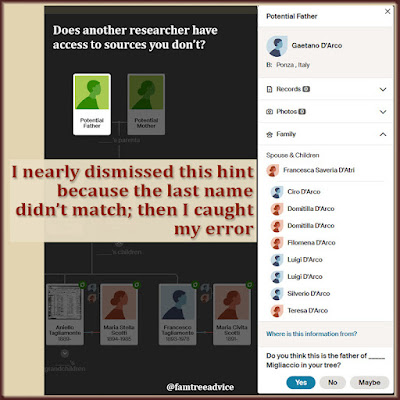

3. See Who Other Researchers Believe to Be Ancestors

Some time ago, Ancestry added Potential Father/Potential Mother hints. These show up in your tree as bright green icons. Click a potential parent, then click Review Details to see the source of the hint. I found these hints for my uncle's grandmother. I had her last name, but not her first name.

|

| Rarely do I believe a potential father/mother hint. But this family tree showed extensive genealogy research. |

The hint for her potential father had a completely different last name. The hint for her potential mother showed the same family, but it had a document image as a source. This is worth reviewing. There isn't a direct way to get to the source tree, but if you click "Where is this information from?" you can see the name of the source tree and the owner. You can then do a Member Search for the owner and find the tree to review.

When I went to that tree, it was clear this person had done extensive research on my uncle's family. The last name I have for my uncle's grandmother may be wrong. I'm horrified to say that I have know idea of my source for that name.

This potential father/potential mother hint seems valid. But I won't simply accept the hints. Instead, I'll explore this person's tree and try to recreate her work.

The vital records for my uncle's hometown are available online now, but they weren't there a year ago when I last looked. This person seems to have found church records. I'll contact her and hopefully we'll collaborate. If she's right, I've opened up an enormous new branch for my uncle's family. This was a great hint.

One of the worst things you can do when building your family tree is click to accept every hint. They're called hints for a reason. They are suggestions of where to look.

Use hints as search shortcuts. Use hints to find distant relatives. Use hints to expand your tree. But do these things carefully to keep from going in the wrong direction.

And speaking of hints:

In response to the first comment below, Antenati blocked us from being able to download high-res images. I've asked them to please put in a download button like FamilySearch does. I'm not holding my breath.