|

| My grandfather Adamo Leone (right) and his younger brother Noé. |

Nothing.

In conversations with my mother and aunt, I learned that my grandfather had a brother Noah (Noé in Italian) and a sister Eve (Eva in Italian). That was good for a chuckle because my grandfather was Adam (Adamo in Italian).

Adam and Eve and Noah? Come on!

This lack of detail made me want to research Adamo's hometown of Basélice in Benevento, Italy, more than anyplace else. (See "Why I Recorded More Than 30,000 Documents".)

The Specifics of Your Ancestral Hometown

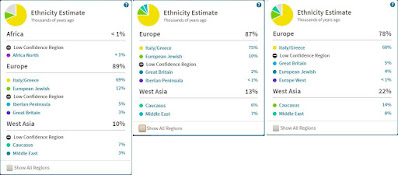

As I began to document the vital records from Basélice for the years 1809 through 1860, I spotted some patterns:

- Most couples married at an average age of 25 years.

- Most couples had their first child within one year of marriage.

- Most couples continued to have children every two or three years until the woman was roughly 45 years old.

- The average number of children per couple was six to eight.

- If a man was widowed, he was likely to marry a much younger woman, and father another six to eight children.

Something's Not Logical

Recently I was able to access and download Basélice vital records for years beyond 1860. When I located my grandfather's 1891 birth record and his parents' 1881 marriage record, something didn't add up.

How could his parents, Giovanni Leone and Marianna Iammucci, have been married for 10 years without having a child? Adamo, Noé and Eva were born in 1891, 1895 and 1898, respectively. Their mother Marianna was 42 in 1898.

It seems fine that she had her last child a little while before her childbearing years ended. But the 1881 to 1891 childless gap made no sense based on my knowledge of their hometown.

So I began searching. The other night I found them!

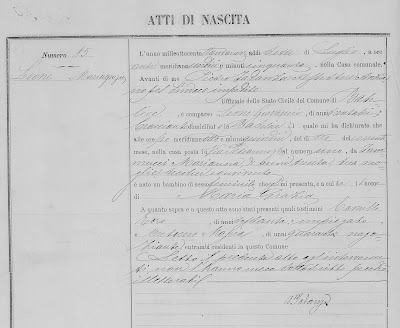

|

| My surprise great uncle Giuseppe Leone's 1883 birth record. See his marriage annotation in the right column. |

My grandfather never mentioned them. But now I know he had an older brother Giuseppe (born in January 1883) and an older sister Maria Grazia (born in July 1889).

My mother can't believe it! She said he never spoke about his life in Italy, and he only mentioned his siblings Eva and Noé.

In the column of Giuseppe's birth record a note says he married Maria Castaldi in August 1914. I have no further details, but I do know Giuseppe did not die in World War I. (Here is a website where you can search for Italian casualties of WWI.)

|

| My surprise great aunt Maria Grazia Leone's 1889 birth record. |

I'll never know why my grandfather didn't mention these siblings. Maybe Maria Grazia died when my grandfather was a little boy or before he was born. But what about big brother Giuseppe? I do hope I'll find out what became of him.

Many times in this blog I've encouraged you to gather every document you can from your ancestral hometowns. (See the links at the bottom of this article.) You could be related by blood or marriage to most of the town.

Use This To Your Advantage

The Giuseppe and Maria Grazia Leone story is another reason to look closely at every genealogy record from your ancestor's hometown.

- Find out at what age couples married and had children.

- See if your ancestral family has a big gap in years between children's births.

- Look in the town's birth and death records for babies who were stillborn or died as infants.

Maybe you'll find a shocking, previously unknown great uncle or aunt for your family tree, too!