My son is getting interested in his family history! All these years, I'm sure he saw my hobby as "mommy being crazy for dead people".

I sparked his interest when I said he was one-eighth Polish. That gave him something in common with his Polish girlfriend. Now he's pushing me to find out all I can about his father's mother's father's family tree.

The tough part about the Stefaniak family is they came to America so early, their ship manifest doesn't include a town name. I haven't found naturalization papers, so I'm working with less than perfect sources.

I have found:

- An 1890 ship manifest saying Mr. and Mrs. Stefaniak are from Prussia

- A 1900 and 1905 census saying they're from "Poland (Ger)"

- A 1910 census saying they're from "Ger/Polish"

- A 1920 census saying they're from West Prussia and speak Polish

- Their youngest son's 1930 census saying his parents are from Germany

- The same son's World War I draft registration card saying his father's birthplace is Poland (state or province), Germany (nation)

|

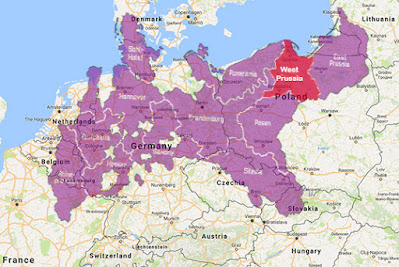

| Rough overlay of Prussia (purple) on today's map, highlighting West Prussia in red. |

I'm sure my son will push me to find more genealogical documentation. In the meantime, I have to ask: What's the deal with Prussia? What area was called Prussia in 1890. How exactly did the German/Polish border shift between 1890 and 1940?

A website called the International World History Project has an essay explaining the history of Prussia (http://history-world.org/prussia.htm). Here are the highlights as they relate to the Stefaniak family:

- The people known as Prussi lived around the Vistula River that cuts down the center of today's Poland. The Germanic people kept trying to convert the Prussi to Christianity as early as the 10th century.

- Centuries later, there were ongoing tensions between Germany and Poland. West Prussia had become part of Poland. East Prussia became independent of Poland.

- In the 1700s the Kingdom of Prussia became an enormous power in Europe under King Frederick and his heirs.

- In 1890 when the Stefaniak family came to America, Prussia was a kingdom within Germany under the imperial chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Prussia consisted of a big chunk of the northern parts of today's Germany and Poland. On a map of Prussia in 1890 I can see that West Prussia—as the 1920 census noted their birthplace—includes the area around today's Gdansk, Poland.

- After World War I—after the draft registration card said Mr. Stefaniak was from the state of Poland in the nation of Germany—West Prussia was lost to Poland.

- Prussia ceased to exist in 1947.

This world history solves a family mystery over whether this branch of the family was actually German or Polish. Ethnically, they were Polish. They came from the area that is today's Poland. Their only association with Germany is that their kingdom was part of the nation of Germany at various times.

Now my son can confidently tell his Polish girlfriend that he is one-eighth Polish.

When you come from a place that no longer exists, it feels good to finally be able to put a pin in that map and call it your ancestral homeland. How can you apply this type of history lesson to your own family tree?