I created this blog with a single thought:

If we amateur genealogists follow some basic rules, our family trees will be so much better.

I listed out the primary keys to high-quality genealogy research:

- Know exactly where your people are from

- Analyze each document carefully before attaching it to your tree

- Cite your sources as you go

- Develop a strong, logical system of document-naming and filing

Let's take a look at how you can put these keys to work for you today.

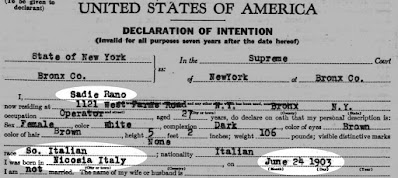

Know Exactly Where Your People Are From

If you don't know exactly which town your ancestor was born in, you can't find their birth record. You may not find their marriage record. You might download records from a genealogy site and never know they're for the wrong person.

|

| My late step-grandmother's naturalization papers told me her story. |

Look for evidence of the town of origin right away. It may be on military records, a passport application or naturalization papers. Knowing that town, you can now reject hints pointing to someone from the wrong place.

Analyze Each Document Carefully Before Attaching it to Your Tree

My tree has so many people with the same name. My grandfather had two first cousins. All three of them were named Pietro Iamarino.

So before you attach a record to your tree—even if you think it's such a unique name—analyze all the other facts. Does everything about this record make sense for your ancestor? Or are there too many facts you know don't match your person?

Keep some basic logic in mind. A dead woman can't give birth or get married. A woman can't give birth to two babies a month apart. A man can't become a father more than nine months after he dies.

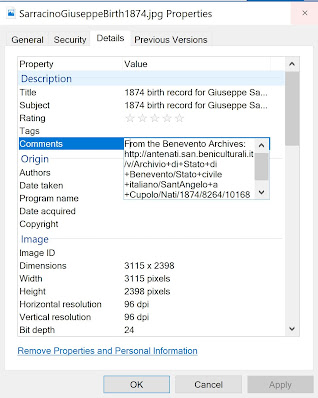

Cite Your Sources As You Go

|

| You can add facts to your images. |

When we begin this genealogy hobby, we're excited by each new name and date we find. And, oh, those ship manifests and census forms! They couldn't make us any happier.

It's common to grab those facts and documents and forget about citing your sources. "It's the 1930 census. Isn't that good enough?"

No, it isn't. Picture this: One day you realize your uncle lived on the same street as your grandmother. You can't find him in a search. If you could just get back to her census form online, you're sure your uncle would be on the next page. If only you'd recorded some facts and a URL.

Put a stake in the ground today. Going forward, you're going to add citation info to each fact and document you add to your family tree.

And then spend a few weekends cleaning up your early work. Make that tree better.

Develop a Consistent System of Document-naming and Filing

|

| Develop your logical filing system. |

At the start of my research, I developed some rules:

- My computer's FamilyTree folder contains a sub-folder for each type of document:

- census forms

- vital records

- city directories

- draft cards

- ship manifests

- naturalization papers, etc.

- Each file name follows the same format. Generally, it's LastnameFirstnameYear.jpg. Since I keep all vital records in one folder, they are more specific: LastnameFirstnameBirthYear.jpg or LastnameFirstnameDeathYear.jpg.

- Census records are named for the head of household: LastnameFirstname1930.jpg. This is true of a ship manifest containing a whole family, too: LastnameFirstname1922.jpg.

When I learn something new at work, I try to apply it to my genealogy hobby. For example:

- I work with Excel all day long. So I catalog my thousands of genealogy records in a single spreadsheet.

- I store work files on OneDrive so I can access them from another computer. Now I store my tens of thousands of Italian vital records in a OneDrive folder so it's backed up instantly.

Be smart, logic and efficient in your hobby. You'll still have all the fun you want, but you'll leave behind a priceless legacy: Your impeccable family tree.