You've downloaded thousands of vital records from your ancestor's birthplace. How do you find your people in all those files?

My genealogy research changed dramatically in 2017. I decided to put my U.S.-based research on hold. Why? Because a new door opened wide. Now I have access to my ancestors' birth, marriage and death records in the old country.

Finally! I'm able to take my great grandparents back many, many generations. So far, I've discovered the names of:

- 4 of my 8th great grandparents

- 7 of my 7th great grandparents

- 34 of my 6th great grandparents

- about half of my 128 5th great grandparents

And I will discover many more.

A brief explanation: FamilySearch.org ended their microfilm program. They used to send rolls of microfilm to your local Family History Center. You could visit these rolls during your center's limited hours and view them on antiquated machines.

But in 2017 they began digitizing everything.

Earlier, I spent

5 years viewing microfilmed vital records from my grandfather's hometown. I typed all the important facts into a laptop. Suddenly those thousands of records are available as high-resolution images online. Free! And so are records from the towns of all my ancestors. You can find them on FamilySearch and on an Italian website called Antenati (ancestors).

I started viewing images from my grandfather Iamarino's town and downloading them. One by one. It was going to take forever!

Then I learned about a simple program called GetLinks. This program runs on any type of computer. It's compatible with FamilySearch and Antenati. For a full explanation and a link to the program, see

How to Use the Online Italian Genealogy Archives.

Now I have well-organized image files from all my ancestors' hometowns. They range in time from 1809 to as late as 1942. But they include rewritten documents of births and deaths from the 1700s. That's how I've found such early ancestors.

|

| Simplify your search by organizing your downloads. |

I'm limited to documents written as early as 1809 only because it's Italy. If your ancestors are from other countries, you may find much older records on FamilySearch.org.

So let's say you've downloaded thousands of images containing oh-so-many of your ancestors.

- How do you find your people?

- How can you efficiently pull out the people and facts you need?

- What's the best way to find your needles in those haystacks?

I'm approaching my 8 haystacks (individual Italian towns) in 3 different ways. You might choose one or two, or want to do them all.

1. Most time-consuming; best long-range pay-off

I'm typing the facts from each document into a spreadsheet. In the end, I'll have an easily searchable file. Want to locate every child born to a particular couple? No problem. Want to find out when a particular 4th great grandparent died? No problem.

But it is slow-going. I've completed about 6 years' worth of birth, marriage and death records for one town. I return to this project when I'm feeling burned out on a particular ancestor search and want a more robotic task to do.

There is another benefit to this method. Spending this much time with the documents has made me very familiar with the names in my ancestors' towns. I can recognize names despite the awful handwriting. And when a name is completely unfamiliar, I often discover that the person came from another town.

|

| A well-organized spreadsheet is best for making records searchable. |

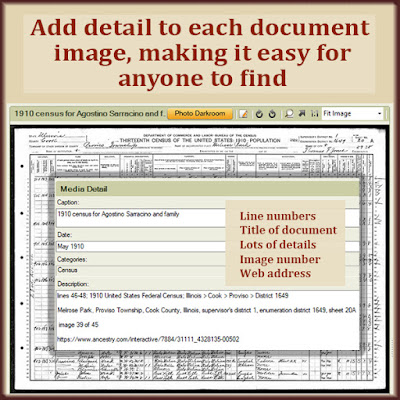

2. Takes a few extra seconds; pays you back again and again

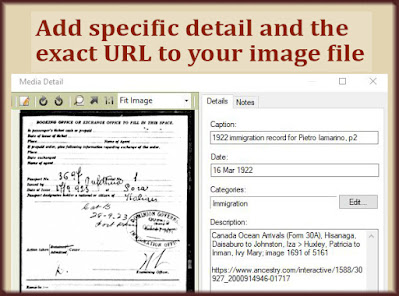

Whenever I find a particular record, I like to edit the name of the image file to include the name on the document. If it's an image of a single birth record, I add the baby's name to the end of the file name. If the name is common, I also add the baby's father's name. (I use the Italian word "di" as a shorthand for "son of" or "daughter of".) If it's an image of 2 birth records or a marriage record, I'll add both names to the file name.

The benefit of renaming the files comes later. When you're making another search in the future, the renamed file can save you time. You can either spot the name you're looking for, or use the search box in that file folder. You can even use the search box at a higher folder level.

Imagine you're looking for my grandfather's name, Pietro Iamarino. You can search his entire town at once and let your computer find every file you've renamed to include "Pietro Iamarino".

When I began downloading the files, I renamed each file containing anyone named Iamarino. Now I can always find the Iamarino I want. Quickly.

|

| Adding people's names to the file names makes the collection searchable. |

3. Efficient, fast and fruitful; makes you want to come back

To my mind, this is the most important lesson. You'll be more efficient at finding what you need in this massive amount of files if you

put blinders on.

Search with a tight focus. Ignore the people in the index with your last name. You'll get back to them. But at this moment, when you're searching for someone in particular, don't look at anyone else. Zero in on that one name and complete your search.

Use this focused approach and find your ancestors faster. The moment you find them, rename the file and get that person into your tree.

My many folders of vital records hold countless discoveries for me. But I've found that choosing one family unit and searching only for them is highly effective. Here's an example.

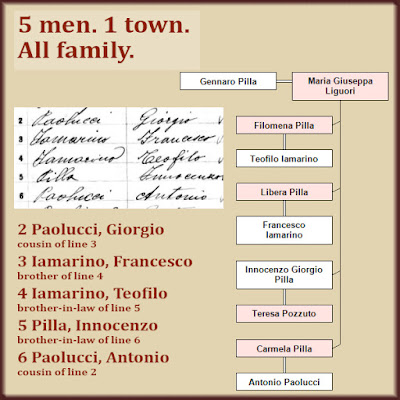

I've found the birth record of a particular 2nd great grandparent. I know their parents' names (my 3rd great grandparents), but I don't know when they married or their exact ages. I'll search the surrounding years for more babies born to this couple. Now I'm putting together their family. I'm also trying to identify which is the eldest child. Now I can search a year before the eldest child's birth for the couples' marriage. There I can find their ages, and possibly see a rewritten copy of their birth records.

With that set of marriage records and my 3rd great grandparents' birth records, I've now discovered the names of 2 sets of my 4th great grandparents. And if they weren't born too early, I may be able to find their birth records, too!

Having built out one family unit as far as I can, I'm even more eager to pick a new family to investigate. Sometimes I'll choose a family with a dead end, and work to find that missing piece of the puzzle.

Which method will work best for you? Or will you combine all 3 as I'm doing?

And speaking of working efficiently: