Do you have an ancestor who moved a number of times? Do you know why?

I'm the daughter of an IBMer. You may know the old joke. IBM stands for I've Been Moved.

My dad started with the company the year before I was born. His first big move took us from the Bronx to Los Angeles when I was 6 weeks old. He took a transfer to New York City before I turned 2. Most (but not all) of his later job transfers allowed us to stay in one house.

But what about our ancestors? Did they also move for the sake of their careers?

|

| A growing steel industry meant real opportunity for men like my grandfather. |

When I look at my family, which has not been here for centuries, there was not a lot of movement. My maternal grandmother's family always lived in the same Bronx neighborhood. Most of their close relatives stayed close to them. They may have moved to different apartment houses, but they were always right there in the Bronx.

But my paternal grandparents (Pietro and Lucy) skipped around a bit. Does the evidence show that they moved for the same reasons my father moved us? For a better job?

Let's look at the data points.

Grandpa's Travels

1920. My grandfather Pietro arrived in America at the age of 18. His Uncle Antonio was in Newton, Massachusetts, just outside Boston. That was Grandpa's first stop. He went to Newton and worked for a baker in his Uncle Antonio's neighborhood.

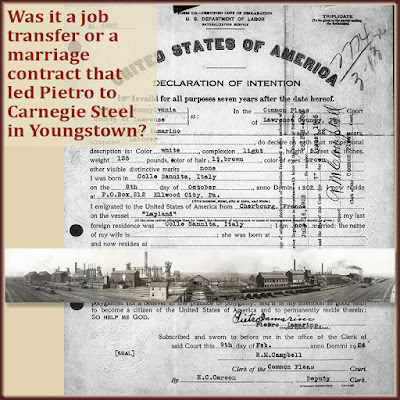

1924. Did the bakery close? Were they not able to pay Grandpa enough money? I don't know. But in 1924 Grandpa filed his declaration of intention to become a United States Citizen. He was more than 9 hours away, working for the National Tube Company in Ellwood City, Pennsylvania.

Ellwood City is a small town in Western Pennsylvania. The National Tube Company formed iron or steel tubes for many uses. Think of tubes as small as the barrel of a rifle or as big as the muzzle of an armored tank.

In 1924 they were growing so fast that they developed a residential area to house the workers. Did Grandpa hear National Tube was hiring? Were they advertising in newspapers across the country?

When he filed his naturalization papers, his home address was a post office box in Ellwood City. He was still there when he became a citizen in February 1927.

1927. Eight months after becoming a citizen, Pietro had moved an hour away to marry my grandmother, Lucy. He was working for the Carnegie Steel Company.

Was this a job transfer after a company merger? Or did his father's cousin (also his future father-in-law) help him get the job? His quick marriage makes me think this was an arranged marriage. The family decided Pietro would be a good match for Lucy, so he took an opportunity to work for Carnegie Steel.

|

| Pietro's documents show where he worked just months before he married. |

1933. Pietro now had 2 young children, including my father. He lived next to his wife's family in the Youngstown suburbs. But he's known to have hated his job. It was dirty work, and he wanted out.

1935. Pietro seized an opportunity to leave the dirty work behind. He moved his family to the Bronx where his Uncle Giuseppe lived. Pietro took a much cleaner job. He was a stone setter at a novelty jewelry factory.

1953. Pietro was 51 years old. Not a great age for a job change. His wife Lucy had cancer and wanted to be near her parents. The family moved back to the Youngstown area. Pietro took a railroad job, but he didn't like it.

1957. After Lucy's death, my father married my mother, and they lived in U.S. Air Force housing. By 1957 my parents lived in a row home in the Bronx. Pietro lived on the bottom floor and returned to working in the cleaner jewelry industry.

Do you have ancestors who moved around? What can the documents tell you about why they moved?

And speaking of following the paper trail: