Dive into your ancestral hometown's documents for extra benefits.

I'm really letting my genealogy freak flag fly lately. A few weeks ago I started an ambitious project to help my research. And it's paying off wildly!

|

| Take a deep dive and become an expert in your ancestral town. |

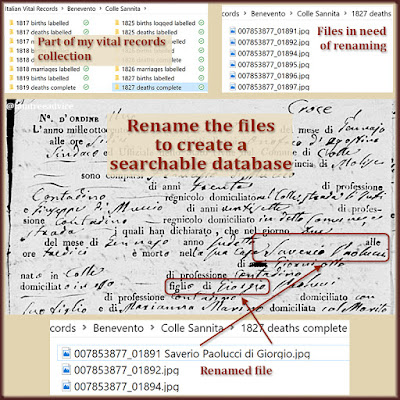

I'm creating a searchable database of everyone who lived in my paternal Italian hometown. (During a large span of time.) First I downloaded all the available records to my computer. Now I'm renaming each vital record image to include the name of the person in it.

- Each birth record's file name now includes the name of the baby.

- Each marriage record's file name includes the bride and groom's names.

- I'm still working through the death record images to add the name of the person who died to the file name.

I don't know how many thousands of vital records from the town are on my computer. They span from 1809–1942. There are gaps. Birth records end in 1915, and there are no marriage or death records between 1860–1931.

But in those thousands of records are the clues I need to piece together my extended family. Let's say I find a birth record for a relative. I've already documented the baby's father's family. But I don't know who the mother's family is. It says she is Angela Basile and her father's name is Giovanni. I can go to my folder of all the town's records and search for "Angela Basile". Then I can open the results to find one who's the right age and has a father named Giovanni. Most of the time I can make a positive ID. It's fantastic.

|

| When the file names include proper names, you can use your computer to search everything in a second. |

Here are 2 major things you can learn by taking a deep dive into your ancestor's hometown.

1. Names of People and Places

Overcome bad handwriting. When you're familiar with your towns' last names, you can recognize them despite bad handwriting. So many times when I couldn't read a name, I figured it out because I knew what to look for.

The same goes for street names. I record exactly where someone was born, if it's on their birth record. I'm so familiar with these records, I can recognize street names easily.

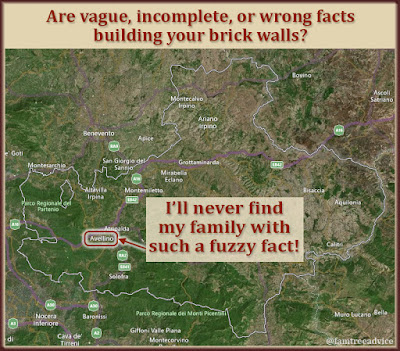

An unfamiliar name. You'll also know when a last name doesn't belong. I have one ancestor named Francesco Saverio Liguori. Based on the vital records, the only people in town named Liguori are his children. That made me wonder if he was from another town. On a hunch, I searched a neighboring town for his 1813 birth record, and I found him! That helped me go back 2 more generations in his family.

Travel companions. When you know all the town's names, you'll recognize them when they're with your ancestor on a ship manifest. Or when they show up next door to your ancestor in a new country.

2. Naming Customs

Carefully examining all the town's documents can teach you about local naming customs.

Foundlings. In my town in the 19th century, abandoned babies were not uncommon. Almost no woman kept and raised her out-of-wedlock baby. The custom was for the mayor to give the baby a name. They sometimes used unusual first names from mythology. But most first names were common to the town, like Maria Teresa or Giovanni.

But last names were different. These names didn't exist in the town. If a foundling boy grew up to have children, the kids took on the made-up name. This is how some new names were first introduced into the town.

Baby-naming conventions. The FamilySearch.org wiki explains baby-naming conventions in your ancestor's culture. In Italy, the rule is to name the 1st baby boy after its father's father, the 2nd baby boy after its mother's father.

When you have 12 kids, though, you need to get creative. Was the baby born on a saint's feast day? Use the saint's name. Is a name popular in town lately? Use that name.

Nicknames and shortened names. A person's death record might use a slightly different name than their birth or marriage record. On their death record you're more likely to see the name they were commonly known as. My 2nd great grandfather Francesco Saverio Caruso may have gone by the name Saverio. I can count on his birth and marriage records to have his full, proper name. But his death record may be from someone reporting that "Saverio Caruso" died.

|

| When you get used to it, spotting the names and renaming the files can go quickly. |

People with multi-part names often went by only one. I'm sure my 6th great aunt, Maria Catarina Colomba Martuccio, wasn't called Maria Catarina Colomba. When I find her death record, I may learn that everyone called her Catarina.

I know we can't all download our town's vital records. You may not have discovered where your family came from. Or their hometown's records might have been destroyed.

But you can apply this name-study to census records, too. Pay attention to the names of the families living near your ancestor in each census. Are you seeing some family names repeat from census to census? Were members of that family born in the same place as your ancestor?

What about immigration records? The ship manifest for your ancestor may have little useful information. But check the names of the people surrounding your ancestor. Do their names match the people living near your ancestor in the new country? They could be relatives from the old country.

This week I'll try to complete my file naming project for Colle Sannita's death records. The act of renaming the files helps me learn the last names and street names from this town.

How I wish I'd been able to do this while my Colle Sannita-born grandfather was still alive!

Be sure to see the follow-up to this article which shows exactly how you can benefit from this project.

Here's some more joy of vital records: