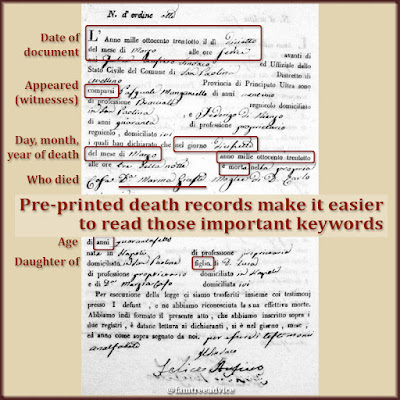

In a recent article I showed you how to read Italian birth records without speaking the language (See Simple Tips for Understanding Italian Birth Records.) In a nutshell, you only need to know which keywords to find, and the info you need will be there.

I suggested you bookmark FamilySearch's Italian Genealogical Word List. This is critical until you're comfortable translating numbers, months, and several keywords. Go to the Genealogical Words section of the page to learn keywords like:

- anni—years, to show a person's age

- anno—year, to show the date

- figlio/figlia—son/daughter

- marito—husband

- matrimonio—marriage

- mese—month

- moglie—wife

- morte—death

- nata/nascita—birth

- nome—name

- sposo/sposa—spouse

- vedovo/vedova—widow

Today let's take a look at Italian death records. As you saw with the birth records, these documents follow a certain format. Once you recognize the format, you can jump straight to the facts you want for your family tree.

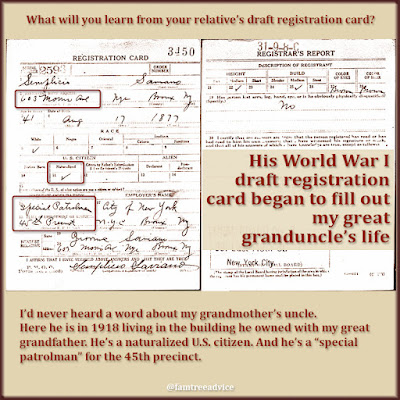

Example 1: A Short Death Record

|

| Knowing what to expect, and where to find it, will help you overcome bad handwriting and a foreign language. |

Our first example is an 1810 death record from Santa Paolina in the Italian province of Avellino.

First, find the date. The document will begin with the date on which the clerk wrote the information. That's not necessarily the date of death, but it will be very shortly after the death.

This document begins with the pre-printed words:

Oggi (today) che sono le (it is)

A handwritten number follows these words. It tells you the day of the month. This one says diciannove (19). It's followed by del mese (of the month), and a handwritten month: Gennaio (January). Next is the year written out in words. This one says dell'anno (of the year) mille (1,000) ottocento (800) dieci (10).

It also tells us the hour the clerk wrote the document, but that doesn't matter to your family tree, does it? This one says ad ore (at the hour) diciannove (19, or 7:00 p.m.).

All those words boil down to: 19 January 1810. That's all you need.

The next section has the names of two male witnesses who may or may not have anything to do with your family. You'll see a name (Tommaso Papa), age (anni settantacinque [75 years]), occupation (bracciale [laborer]), and where they live. Unless you see zio (uncle), avo (grandfather), or cugino (cousin), the witnesses are probably townspeople, not family members.

Second, look for the word morte (death). After the witnesses are the pre-printed words li quali hanno sottoscritta la dichiarazione della morte di (who signed the declaration of the death of). This means the witnesses are testifying about someone's death. Morte is the only word you must find. It's good to know the word dichiarazione or the variant dichiarato. Those words signal to you that the witnesses are declaring whatever follows.

After the word morte is the name of the deceased. The usual format is:

Name of the deceased, age, date and time of death, their parents, their spouse, and where they died.

In this case we see:

- Maria Antonia Censullo (the person who died)

- di giorni due (age 2 days)

- morta nel suddetto giorno (died on the same day [as written above])

- ad ore diciotto (at the 18th hour [6:00 p.m.])

- figlia di (daughter of) Domenico and Angela deMarco (the parents)

- domicilianti in detta Comune (living in this town)

- ed abitanti la stessa strada (and living on the same street)

If we look above at the witnesses, the first lives on Strada Ponticello. The 2nd witness lives on la stessa strada (the same street). We can assume the Censullo family also lives on Strada Ponticello.

The rest of the document is boilerplate legal stuff. All you need from the entire page is this:

On 19 Jan 1810, Maria Antonia Censullo died in her home on Strada Ponticello at the age of 2 days. Her parents were Domenico Censullo and Angela deMarco.

I'm surprised to see this document does not mention the name of the town. This is an unusual oversight that I'd attribute to the date. This document dates back to less than one year after the town began keeping civil records.

Focus on the keyword morte to find the meat of this document.

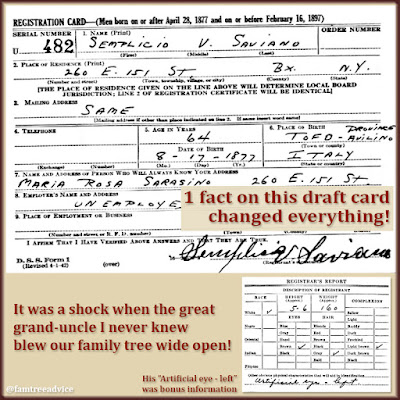

Example 2: A Longer Pre-Printed Form

|

| This type of death record makes it a lot easier to find those critical foreign keywords. |

In later time periods you'll find death records with more pre-printed words. Pre-printed means easier to read. Here is an example from the same town in 1838.

As with all documents, this one begins with the date the clerk wrote it:

L'Anno mille ottocento trentotto (the year 1838) il di diciotto (the day 18) del mese di Marzo (of the month of March) alle ore sedici (at the 16th hour [4:00 p.m.]).

All you need to know is that it's 18 March 1838.

Next we see the name of the town. It says del Comune di (in the town of) San Paolina (actually Santa Paolina) Distretto di Avellino (in the province of Avellino).

After this we see the witnesses' names, ages, occupations, and that they live in the same town. Neither one appears to be a relative because there are no relationship words.

Next we can find the word dichiarato (declared) which leads us into the facts we want.

The witnesses declared that:

- nel giorni diciasette (on the 17th day [the day before the clerk wrote this document])

- del mese di Marzo (of the month of March)

- anno mille ottocento trentotto (in the year 1838)

- alle ore tre della notte (at 3:00)

- é morta (died)

There's that word morte/morta, telling us that the facts about the death will follow.

So far we know when the death happened: 3:00 on 17 March 1838. Now let's find out who died.

The document says é morta nella propria casa. You will see this often. It means the person died in their own house.

The name of the deceased is Marina Giusti, and she has the abbreviated title Donna before her name. The word after her name is moglie (wife). She is the wife of Don Carlo Ciampi. After the large amount of white space we get more details.

Marina was 47 years old (di anni quarantesette). She was born in Napoli. Her profession was proprietaria (owner), and she lived in Santa Paolina. Find the word figlio (son) or figlia (daughter) to see who the deceased was the child of.

Marina was the daughter of Don Luca Giusti, an owner living in Napoli, and Donna Marzia Caso, also living in Napoli. (They've used the word ivi, meaning therein, and referring back to Napoli.)

Once again, the rest is boilerplate. All you need from the entire page is this:

Donna Marina Giusti, a 47-year-old owner, died on 17 March 1838 in Santa Paolina. She was born in Napoli to Don Luca Giusti and Donna Marzia Caso. She married Don Carlo Ciampi.

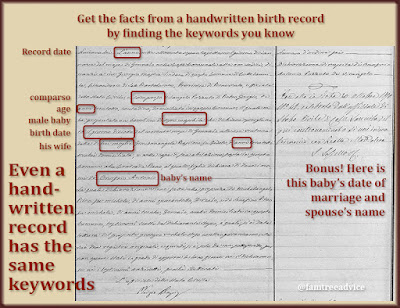

Example 3: A Completely Handwritten Death Record

|

| A completely handwritten foreign death record shouldn't scare you. Just spot those keywords. |

In the 1870s in my ancestral hometowns, the death records were completely handwritten. There was no pre-printed information. Sure, it can seem overwhelming. But the truth is, you're still going to look for the keywords and skip over the parts that don't matter.

This example is the death record of my 1st cousin 6 times removed, Aganice Consolazio. Let's dissect it.

Each death record still begins with the date the clerk wrote the document. This one says:

L'anno mille ottocento settantatre (1873) il di quattordici (the 14th) Gennaio (January) in Santa Paolina, alle ore sedici (at the 16th hour, or 4:00 p.m.).

This document has a lot of formalities. We can skip down 6 lines to find the word comparsi (appeared) followed by details about the two witnesses.

After the witnesses, look for more words about the date. This will be the actual date of death. On this document we see del giorno quattordici del corrente mese di Gennario (the 14th day of the current month of January).

Now we know when they died. Let's see who died and where.

Right after the date of death we see in questo Comune di (in this town of) Santa Paolina. And there is a street/neighborhood address of Contrada Ponticelli. Immediately after that are the words é morta. That's our key to finding out who died.

Aganice Consolazio was sessantasette (67) years old, nubile (never married—that's a great bit of detail), living in Santa Paolina.

Then there's the keyword figlia (daughter). My cousin Aganice is the daughter of Federico Consolazio and Vincenza Ciampi. But we have another important clue before her parents' names. It says figlia dei furono, which tells us both her parents are already dead. If only her father were dead, it would say fu Federico, meaning that Federico is dead. But furono is plural, so both parents are dead. Fu means was, furono means they were. They are past tense now. They have died.

After Aganice's mother's name is the profession medico (doctor). While you might expect this to be Aganice's profession, it is masculine (medico), not feminine (medica). This profession belongs to her late father, my 5th great granduncle, Federigo Consolazio. Aganice's profession would be closer to her name. In this case, there is no profession; only the word nubile to tell us she never married.

The final sentence tells us the witnesses are analfabeti (illiterate). They made their testimony, but they cannot sign the document.

You'll find a lot of similarities among documents across many years. No matter the format, Italian death records will contain the same basic information. The only time you may need to ask for help is an extra paragraph is explaining something unusual.

Bookmark that FamilySearch word list, get used to the look of month and number words, and dive in. You absolutely can do this!