Some of the mistakes I'm seeing on vital records are shocking. No one's perfect, of course. But you'd like to think the clerk recording a birth record got the facts right.

|

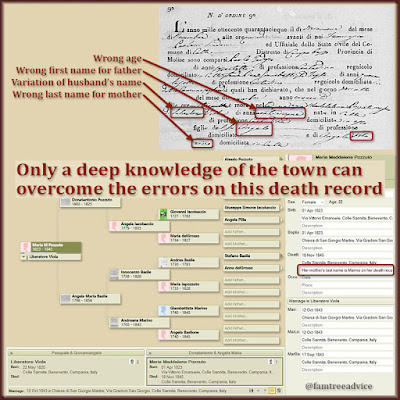

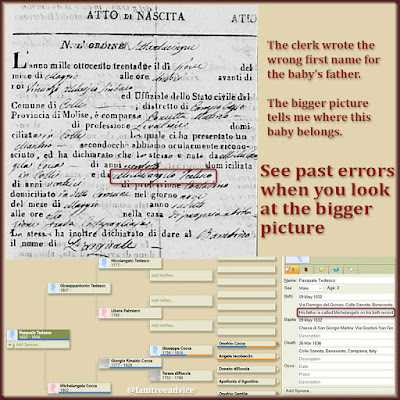

| We want to take vital records as gospel, but human error will always find a way in. Here's how to handle these errors in your genealogy research. |

As I work my way through the vital records from Grandpa's hometown, I'm uncovering lots of errors. The errors fall into a few main categories:

- Wrong date. Sometimes you'll see a February 30th slip in there. Other times the date of birth is a day after the date they wrote the document. Not possible.

- Wrong first name of parent. People with multiple names may go by any one of them. A Giuseppe Nicola Bianco may call himself either Giuseppe or Nicola. I have to keep that in mind when I try to find this person in my tree. But I've seen my ancestor Saverio called Francesco when Francesco was never part of his name.

- Wrong last name of mother. I've had trouble placing a baby in my tree when their mother's last name is wrong on the birth record. I try to verify the right name with the child's death record or the births of their siblings.

- Wrong ages for parents. This is far too common and not the clerk's fault. Before you had to state your birth date regularly, people didn't know exactly how old they were. They're generally in the right ballpark, but sometimes they're way off.

- Wrong last name for baby. This has tripped me up a few times. Somehow the parents' names are correct on the birth record, but the baby's last name is an error.

- Spelling variations. I know my ancestral hometowns, so I know the typical spelling variations to watch out for. Iamarino becomes Marino. Iavasile becomes Basile. Iazeolla becomes Zeolla. These names are sometimes interchangeable.

How to Know What's Correct

As I've mentioned so many times that you're sick of reading about it, I'm working my way through ALL the vital records for Grandpa's hometown. At least 95% of the people can fit into my family tree somehow. As I build out every single family, these errors become plain to see.

The other day I began going through the 1854 birth records. I found one baby, and when I finally located her parents (there was a name error), I saw my note. It seems I'd already found this baby's death record and entered that date. But I couldn't find the baby's birth record (because of the name error). For a birth fact, I had a calculated year based on the age at death, and one of my standard notes in the description field. "Birth record not found."

Now I know why I couldn't find the birth record. The document had an error. But by process of elimination, I know know that the birth record with the error can only belong to this person.

How to Record the Errors

I've made a habit of adding a standard line of text to explain the error. I put this text in the description field of the fact with the error. For example:

- If a birth record has the wrong last name for the baby's mother, I enter: His mother's last name is Marino on his birth record.

- If a death record uses a different first name for a person, I enter: She is called Mariangela on her death record.

If documents provide competing facts, I add a bookmark to the person and a more detailed note. For example, Italian marriage records can include the death record of the groom's grandfather. Many times I've found that it's the wrong record. Right name, wrong guy. But sometimes it's a different date, and it isn't clearly another guy. This calls for a note.

|

| With a broader knowledge of your ancestor's town, you can see past the human error in vital records. |

Rules to Keep in Mind

If you get familiar with the people of your ancestral hometown, a lot of things will become clear to you.

- People didn't always go by their given name.

- People didn't know how old they were.

- People's names can get really messed up.

- If a person died in another town, that town's clerk may have no idea who the deceased's family members are. Or how old they are. It's not like they were carrying a driver's license or had an In Case of Emergency contact on their cellphone.

If you're familiar with the last names in town, you'll be ready to search for a Basile when you can't find a Iavasile. And if you know how the vital records work, you won't rely on a person's stated age unless you see:

- their birth record, or

- their marriage record for which they had to supply their birth record.

Human errors can be so frustrating to your genealogy research. I know I feel better about my choices when I leave a note to point out the discrepancy. If new evidence comes up and proves I made a wrong choice, it's good to see that note and understand how it came to be.

In fact, this falls more into my own human error, but I want to share it. For my ancestral hometowns, the marriage records end in 1860. After that, the clerk usually wrote a marriage notation in the column of the birth record. As I enter a baby into my family tree, I add their future spouse's name and their marriage date. In the description field I enter either, "From her birth record" or "From his birth record." When I find the right spouse's birth record, I change the description to "From both their birth records." That's a nice confirmation when there is no marriage record.

The other day I found that I'd made a wrong assumption about a groom. When I found the right groom, with the same exact name, I had a dilemma. But then I saw my note. For the wrong groom's marriage fact, it said only "From her birth record." Now that I'd found the groom with the matching marriage notation, I knew for certain that the other guy was wrong. I detached him from the bride and her kids.

Remember that mistakes happened a lot. Examine as many records from the town as possible to get a feel for the names and make these errors stand out. And develop your own standard language to let future you know why you did what you did.

Good post. So many people starting out in genealogy expect their family’s last names to be spelled perfectly. They dismiss records if the name is not exact. “My family did not spell it that way so we are not related”

ReplyDeleteCould it be that the people keeping the records didn't have much education and wrote what they heard the way they thought was right? After the French revolution when the keeping of the records went from the priests to the "civilians", the registers became full of horrors. Those in charge had very little or no eduction. This lasted for a while until finally in most villages, the teacher became the village secretary and was put in charge of those important record keeping books. In fact the teacher had to accept the position knowing he (it was always a male for a very long time) would also be the village secretary. He would also get a small stipend from the village for this extra work on top of his salary paid by the government.

ReplyDeleteInteresting info! The fact that the clerks could write at all tells me they were educated. Everyone else in town is signing with an x or printing their name in big letters like a child.

Delete