I have a handful of stock descriptions I routinely add to people in my family tree. Using the same language each time speeds up the process and adds consistency. As I type, Family Tree Maker suggests text based on other entries, and I choose the right comment. Easy.

Some of my stock descriptions include:

- "His brother [Her sister] of the same name was born on this date." Without a death record, this is my reason for saying this child died before this date.

- "His wife [Her husband] remarried on this date." Other variations are "died on this date" and "had a child on this date." Without a death record, these are my reasons for saying someone died before this date.

- "From his [her, both] birth record[s]." I add that as a marriage date description when the date is only available as a notation on a birth record.

- "His [Her] father was in America when he [she] was born." I add that as a birth date description when the birth record notes this fact.

I've always meant to follow up on that last description about being in America. And that's today's project. I'll search for immigration records for fathers who were in America when their child was born in Italy.

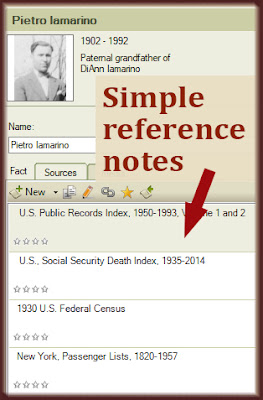

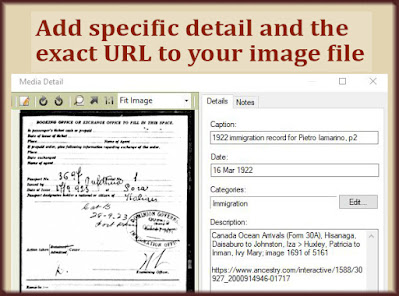

|

| Without this description, I'd never remember to follow up on this immigration fact. |

There's a reason they mention this fact on an Italian birth record. Fathers had a duty to report their child's birth to the mayor right away. If someone else reported the birth, like a midwife or grandparent, the mayor recorded a reason why. Sometimes the father is in another town working. Or he's ill. And sometimes they delay reporting the birth because of terrible weather. But many times, he's gone to America to earn money.

I've been exporting a new GEDCOM file from my family tree each day because my tree is growing so fast. I'm currently working through every available vital record for my maternal grandfather's hometown. Almost everyone fits into my tree. (See "The Method to My Genealogy Madness.")

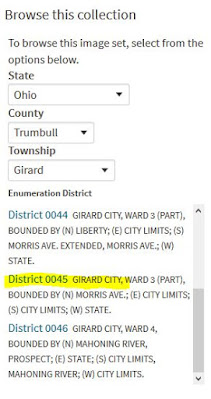

Using a text editor, I can open my GEDCOM file and search for each instance of "in America when." There are 63 of these descriptions. The first one is for my 4th cousin 3 times removed, Domenico Saccone. I searched Ancestry for his father Giuseppe Antonio Saccone, entering his year and place of birth, his wife's name, and his parents' names.

With minimal effort, I found three different crossings for Giuseppe Antonio Saccone:

- 1893, going to New York

- 1900, along with his eldest son, going to join an uncle in the Bronx, NY

- 1906, going to join his son-in-law in Connellsville, PA

This adds 3 new and unexpected data points to this family, plus a lead on that son-in-law. I didn't expect a man born in 1852 to make all those crossings. For my Italian hometowns, the men who sailed to America were a lot younger than Giuseppe Antonio. One very notable exception is my 2nd great grandfather. Born in 1843, Antonio Saviano made 4 trips to America, finally bringing his whole family with him in 1898.

Make stock descriptions a habit, and you'll leave yourself breadcrumbs for future research.

As I work through the 63 descriptions of a father in America, I'll update these notes. I'm thinking, "His father was in America when he was born. Immigration facts documented."

|

| Using a handful of standard phrases in your family tree eliminates confusion and doubt. |

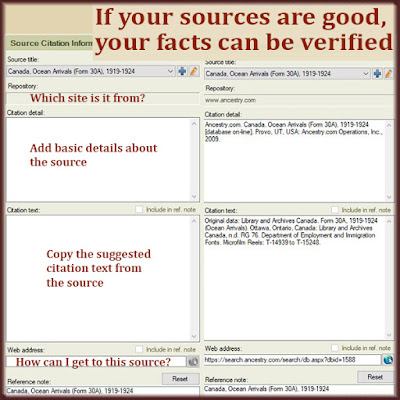

Another type of description I add saves me from a lot of confusion. Sometimes I'll note that a person died before a certain date, but it isn't obvious where that date came from. Note: It would be obvious if I had source citations for every fact in my family tree, but I've got more than 64,000 people in my tree. I'll get to it!

One example is Giorgio Pozzuto who was born in 1788. I've documented his marriage and the births of his 8 children. But there's no death record for him. (The town's available death records end in 1860.) Then I noticed his grandson's 28 Dec 1868 birth record says Grandpa Giorgio is dead, so I took note of it. I gave Giorgio a death date of "Bef. 28 Dec 1868," and a description of "From his grandson Francesco Saverio Giovanni Pozzuto's birth record."

That very specific description ends any confusion about the source of this fact. Plus, when I add his grandson's birth record and source citation to my family tree, I can copy the source and paste it on the grandfather's death date.

I know I have more examples of stock descriptions in my family tree. Looking through my GEDCOM I see:

- "From his [her] grave marker." (See "Inspiration Leads to a Family Tree Growth Spurt.")

- "From her [his] obituary." (See "How Much Can Your Learn from Your Relative's Obituary?.")

- "From her [his] funeral card." (See "This Memento Provides Key Facts for Your Family Tree.")

- "Date based on age at death."

As more vital records come online, I'll revisit many of these comments to see if I can add a more reliable source.

What other types of breadcrumbs would you leave in your family tree?