Years ago I downloaded old photos of five ships that brought my relatives to America. I remember these photos being easier to find back then. Last weekend, I was thinking about the ships that carried my grandfathers' to New York. Was there more to learn about their emigrations?

The RMS Lapland

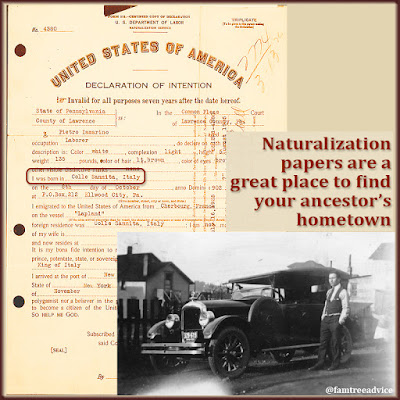

I don't know why Grandpa Iamarino didn't sail out of Naples. Everyone else from his Southern Italian town did. He traveled way up to the northern coast of France and sailed from Cherbourg. That's an 18-hour train ride today! I had a photo of his ship, the Lapland, but a little research told me more.

|

| No matter how many genealogy facts you find on your immigrant ancestor's ship manifest, there's something else you need to search for. And it can enrich your family tree. |

The Lapland belonged to the Red Star Line based in Antwerp, Belgium. The majority of the ship's passengers in November 1920 boarded the ship in Antwerp. Most of them came from Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary. The ship made one more stop in Cherbourg, France, before heading to New York Harbor. About 300 Italians boarded the ship in Cherbourg, including Grandpa Iamarino.

Why did these 300 Italians sail from Cherbourg instead of Naples? I found an American whose German ancestor sailed from Cherbourg. He learned at a museum in Cherbourg that the shipping companies had to compete for customers. With a price war going on, the cheap fare from Cherbourg could have been worth the long train journey. The Red Star Line may even have covered the train fare.

The SS Caserta

My Grandpa Leone lived one town away from Grandpa Iamarino and sailed to New York twice. I realized I didn't have a photo of either of his ships. He first came to New York in 1914 with permission from his local draft board. Military registration and service were mandatory in Italy when a man turned 20 years old. Grandpa Leone registered in 1911, served, and suffered an injury in 1912. In 2018 I photographed his military record in the archives at Benevento to get these details.

I searched online for a photo of the SS Caserta, and I searched Wikipedia to learn about the ship. This one ship had four different names in its 24-year existence. The Bucknall Line shipping company launched her in 1904. They sold her to the Lloyd Italiano shipping line in 1905. My grandfather sailed on her in 1915 as the SS Caserta. The Navigazione Generale Italiana shipping company took possession of the ship in 1918. During World War I, the Caserta served as a troopship, carrying U.S. troops to France.

Part of the Caserta's history seems to fill in a blank in Grandpa Leone's story. His immigration record tells me he returned to Italy to fight in World War I in August 1915. Since we don't have outgoing U.S. ship manifests available, I don't know which ship took him back to Italy. I found out the Caserta and other ships carried Italian Army "reservists" back to Naples.

Were these Italian men feeling patriotic? Or did their government track them down in the States? Grandpa Leone went back to Italy, fought, got captured, and spent a solid year in a prison camp in Austria. After he recovered, the Italian government paid for him, and many other men, to sail to America if they wished.

The USS Henry R. Mallory

At first I thought it was a mistake, but the ship Grandpa Leone took back to New York in early 1920 had belonged to the U.S. Navy. The USS Henry R. Mallory served as a military transport ship during both World War I and II. Between wars, the Mallory Lines shipping company operated the ship.

The Italians on board with my grandfather have a rubber stamp beside their name on the ship manifest. The stamp says "RES. USA. RET." I have read that the Italian government paid for the passage of its military members. But I see entire families with the rubber stamp, which I interpret as "Reserved. USA. Returnee."

On closer look, I see that many men on Grandpa Leone's page have "reservist" (not Italian) in the language column. On the previous page, someone penciled in "Reservist" at the top of the column. Then they added ditto marks all the way down the list.

They must all be Italian Army soldiers and some of their family members. The Italian government would have reserved and paid for their passage.

Now It's Your Turn

Take another look at the ship manifests for your closest immigrant ancestors. Take note of the name of the ship and the year. Now search online for both a photo and some history of the ship. It can help your search if you put SS in front of the ship name. What can you learn about your ancestor's passage, and what other research will that lead to?