I can't be the only genealogist who treasures names. I had no particular love of names before I got into genealogy. But once I started viewing vital records from my Grandpa Leone's hometown, it opened up a world of wonder.

|

| What's in a name? When it comes to genealogy research, absolutely everything. Find out how to honor the names in your family tree. |

This was somewhere around 2008, and I remember being smitten with certain names. Last names like Lapastoressa and Pisciotti were fun to say. First names like Serafina and Elisabetta sounded musical.

After years of researching a handful of Italian towns, I know which last names came from which town. Even my husband recognizes some names from having seen them in the towns' cemeteries. This name recognition comes in handy when you're looking at your DNA matches. Even those with the slimmest of family trees. It can help you find your connection.

Today, let's look at the power of names in genealogy research.

When Too Many People Have the Same Name

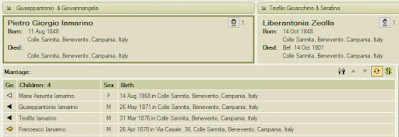

It's funny when someone writes to ask me about a particular person in my family tree. I have to ask, "Which one? I have at least 6 people with that name." Different cultures have specific baby-naming conventions. And that can lead to a lot of relatives with the same name.

Don't worry. There are techniques you can use to make sure you're putting the right person in the right nuclear family. Here's a case study in "Same Name; Which Ancestor is Which?"

When One Person Used a Few Names

Because I fell in love with the Italian names in my family tree, I have a few rules about recording those names. Spellings can change over the years, and someone with two or more names may not go by their first name. A man named Giovanni Antonio Bianco may use the name Antonio Bianco. My great grandmother was born Marianna, but she often used the name Mariangela. She had an older sister Mariangela who died very young.

I choose to respect the original name. In my family tree, I list everyone's name as it appears on their birth record. I'll use the birth fact's description field in Family Tree Maker to note name variations. I admit, I did not record the mistaken name given to my mother at birth. Grandma was out cold, and Grandpa told the midwife the wrong name. This still causes Mom trouble when it comes to getting official government documents. And guess what? That wrong name connects back to Grandpa's mother, born Marianna but called Mariangela.

See which name rules you'd like to adopt in "4 Rules for the Names in Your Family Tree".

Find the Maiden Name to Expand the Family

I'm thankful that women in Italy kept their maiden name for life. If I'd known that before my marriage, I'd have gone back to my maiden name, as impossible as it is for people to handle. It was only when these women came to America that they adopted their husband's last name. They adapted to the local cultural norms.

For a long time, my great grandmother Maria Rosa's line was a dead end. As I began building my family tree, my aunt told me that Maria Rosa's last name was Caruso. That helped me find her many brothers who came to New York State before her. But I couldn't find anything to tell me her mother's name.

A few clues pointed to her first name being Louise (Luisa in Italian), but I didn't know her maiden name. It was a glorious victory when I merged different resources to come up with her most likely last name. Then I proved it, and at last I built her full family tree.

To find out what those clues were and where you can find them, see "These Tips Find Missing Maiden Names".

The names of your ancestors infuse cultural heritage into your family tree. Honor them by recording them the right way and sharing them with your relatives.