Last week we covered 5 out of 9 bonus facts you can find on Italian birth records. They can be game changers! Here are the rest of them.

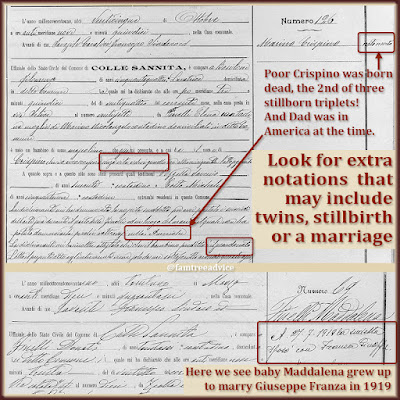

6. Multiple births

Look next to a baby's given name on their birth record for gemello (twin). In a paragraph after the baby's name, look for "é il primo nato" (is the first-born) or "é il secondo nato" (is the second-born). Of course the birth order is the same as the record order.

|

| If baby is a twin (or triplet), look for special wording. Also, did baby grow up to marry? Look for who and when, and sometimes where. |

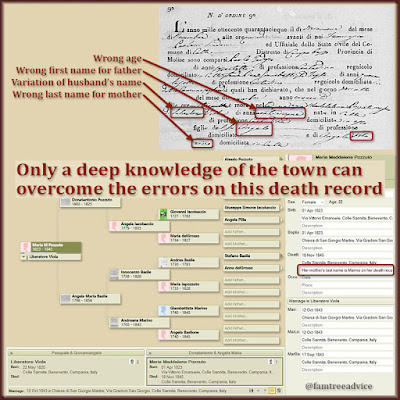

7. Baby's dead father's date of death

This is a (sad) bonus I discovered last week. Many times when a midwife reports the birth instead of the father, the documents tells us why. Typically I see:

- the father is in America

- the father is out of the country

- the father is ill

- the father is in jail

But sometimes he didn't present the baby because he's dead. And you may find his death date on that birth record. That's fantastic if that year's death records are unavailable to you.

On Libera Filomena Zeolla's 1887 birth record, the levatrice (midwife) presents the baby. The document says Libera was born to Damiana Palmiero, the widow of Giovanni Zeolla. So we know Giovanni died shortly before his baby was born. But in a bonus paragraph we see:

That translates to: The declarant presented this baby, having witnessed Palmiero giving birth, and instead of her husband, because he died on 17 August 1886.

|

| It's always sad to see a baby born after dad died. Silver lining: This record tells us his date of death. |

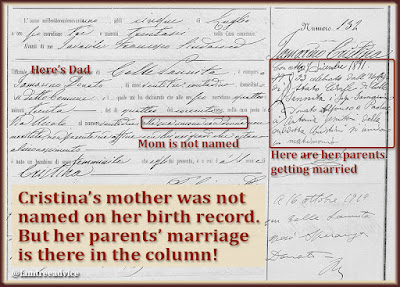

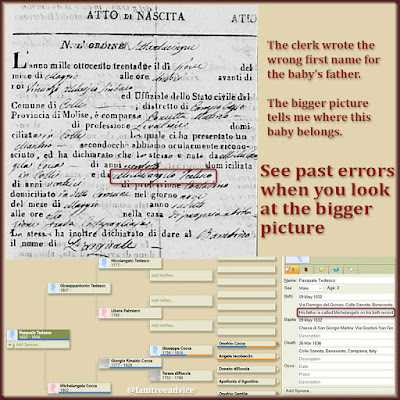

8. Marriage notation

It's great when your ancestor's birth record has their marriage notation in the column. If you already know who they married, this confirms you've found the right birth record.

The marriage notation can include:

- Date of marriage

- Town of marriage

- Spouse's name

In another town I know, if a woman married an out-of-town man, her birth record even includes his parents' names. Bonus!

If your person married more than once, you'll see multiple marriage notations. They made these notes at the time of the marriage when the bride or groom had to prove their birth and parentage. While the clerk is getting that proof, he can add the marriage notation.

9. Baby's father died in the war

One genealogy project that's waiting for my attention is identifying men who died in the war. I photographed their names on a monument in my ancestral hometown's piazza. I can find their military records online.

As I add babies to my family tree from the early 1900s, I'm finding a few records that note the baby's father died in the war. When I see that, I rush to get the father's military record.

|

| Seeing this "died in the war" notation tells you to look for the soldier's military record. |

This notation in the column of a birth record will say something like:

That translates to: The parent died in the war on 27 Oct 1917.

This particular soldier, Angelo Giovanni Mascia, had at least 3 children. I found this important note written on his sons Antonio and Giovanni's birth records. His first child was stillborn, so he did not get the note. I'd guess the note is there because the surviving children are due some compensation.

It's very easy (with practice) to pull the important facts from an Italian birth record. Be sure to look at the rest of the document, especially after 1865, for more details. Be on the lookout for notations in the columns and a paragraph written after the baby's first name.

Now you're ready to cash in on all these bonus facts!