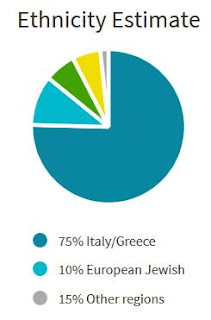

In my last post I spoke about how diverse my DNA results are despite having roots only in Italy going back at least to the 1600s. I've also written about why our ancestors may have left their homeland.

Today I found a wonderful Map of Human Migration, courtesy of the National Geographic Society. It supports several other sources I've read about how Italy (and Europe) was long ago populated by people from the Middle East—an area National Geographic refers to as the Fertile Crescent.

|

| Map of Human Migration |

It's a useful map for so many ethnicities, and if you choose your ancient ancestors' most likely route (I chose the one pointing to Italy), it also tells you your probable haplogroups. Particular similarities in DNA strands can be inherited together, meaning that they can be passed down generation after generation. Ethnic groups can retain this DNA similarity for so long that you may have markers in common with people who are native to a particular region today.

The National Geographic site tells me that the Middle East to Europe migration path may indicate the following haplogroups: H, J, K, N, T, W, G, E. The Family Tree DNA site provides detailed explanations of each haplogroup. The letters above point to Europe and pan-Eurasia, but G and E are not defined on this page.

Be sure to explore the Map of Human Migration and see who populated your ancestor's homeland.