Results of Following Genealogy Best Practices, Part 3

This is the third article in a series about the benefits of following genealogy best practices. (Read about more genealogy best practices in part 1 and part 2.)

Last November my 5-year-old computer started misbehaving. I couldn't risk losing all my genealogy data and business assets, so I acted quickly. I secured my data and made multiple backups while I waited for my new computer to arrive.

Five months later, I'm faithfully sticking to my data-safety plan. I hope this will inspire you to do the same before disaster strikes.

1. Stick to an Easy Back-Up Plan

To make sure my family tree research is protected, I created a simple back-up plan. Each Sunday I run down my short list of which files to back up to which location. Here's the entire list, just to prove how simple it is.

LAST BACKUP 4/15/2018

- Back up to OneDrive:

- (automatic) Antenati files

- (manual) E:\FamilyTree

- Back up to external drive:

- C:\Users\diann\Documents\Quickbooks

- C:\Users\diann\Documents\Outlook Files

- E:\ everything EXCEPT FamilyTree

I have two main backup locations: a 1 terabyte external drive and 1 terabyte on the Microsoft cloud (OneDrive). That's a lot of space. A lot of space.

I love how the folders I set as OneDrive folders are continuously updated on the cloud. I don't have to save a spreadsheet as I'm working on it. And if I rename files or folders, that's synchronized with the cloud version. No effort needed.

|

| My OneDrive folders are backed up automatically. |

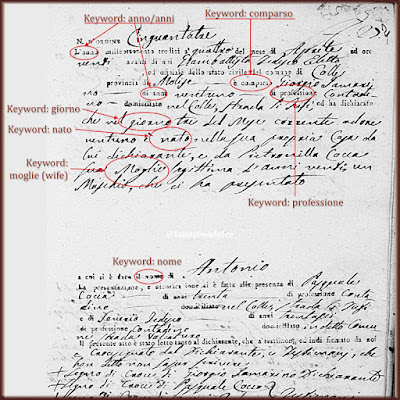

The thousands and thousands of Italian vital records I've downloaded from the Italian genealogy archives site (Antenati) are always backed up to the cloud. So are my genealogy tracking spreadsheets.

What I still update manually are the new document images I've downloaded and added to my family tree. I also copy my complete Family Tree Maker file, its automatic backup, and my 2 most recent manual backups there. Once a week I simply drag the newest files to my cloud storage.

The rest of my backup list shows me the few locations of files to copy to my external drive. By sorting my file folders by date, I can see what's new and complete all my backups in about five minutes.

2. Take Advantage of Free Cloud Storage

I've explained how I'm using my 1 terabyte of Microsoft OneDrive. You don't have that? Try a search for "free cloud storage providers".

Note: I don't keep anything on the cloud that's personal. My email and financial records are not there. Only publicly available genealogy documents are there. So don't be paranoid and brush off this idea. You can do it safely.

Take a look at Google Drive and Dropbox. If you don't want to pay for storage, you can combine different free spaces. If you spell that out in your backup list (like mine above), you'll always know what goes where.

3. Keep Track of Your Genealogy Records

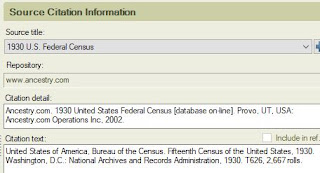

I believe strongly in keeping an inventory of the documents I've attached to people in my family tree.

I've also got:

- a complex spreadsheet where I'm documenting the thousands of vital records from my ancestors' 5 Italian hometowns

- an ancestor spreadsheet listing the name and Ahnentafel number of each direct ancestor whose name I've discovered

- a list of Italian words for occupations and their English translations. (See How to Handle Foreign Words in Your Family Tree.)

Anything you need to reference regularly, need to keep track of and want to keep updated, you can store on the cloud. Then you've always got a safety backup.

To safeguard your genealogy treasure, make these steps a habit. Decide which files belong where. Pick a day each week to make a manual backup. If you can remember to brush your teeth each day, you can remember to practice these safety tips.

Be safe out there.

These articles will help you protect your family tree: