If you don't have at least 10 people in your family tree with the exact same name, you may be new to genealogy.

Many cultures follow specific baby-naming conventions—but not always. For example:

- name your first-born son after his paternal grandfather

- name your first-born daughter after her paternal grandmother

- name your second-born son after his maternal grandfather

- name your second-born daughter after her maternal grandmother

My paternal grandparents followed this convention. They named my father and his sister after their paternal grandparents. My mother's family did not follow the rules. If they had, my grandmother and I would both be named Mary Louise.

For help with your ancestors' child-naming customs, follow these links:

If I've left out your ethnicity, try a Google search including the ethnicity and "naming customs" or "naming conventions".

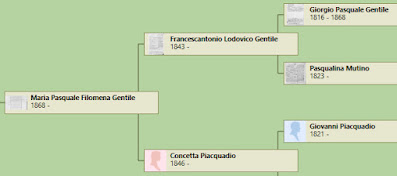

Here's an example of an Italian couple who followed the rules, but put a slight twist on them.

|

| Giorgio and Maria followed the naming rules closely, but not perfectly. |

Giorgio and Maria named their first son and daughter after Giorgio's parents, Onofrio and Lucia. They named their second daughter after Maria's mother, Concetta.

But their 2nd through 5th sons were not named after Maria's father, Francescantonio. Instead, 3 of those sons had the Antonio part of Francescantonio in their name:

- Giovannantonio

- Giuseppantonio

- Antonio

You can use your ethnicity's naming customs to help you place a person in a particular family.

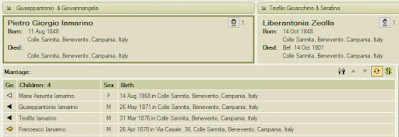

Let's say you have a man named Pietro Iamarino. (I have 11 of them in my family tree.) You don't have his birth or death record yet, so you can't confirm his parents' names. But 1 or 2 of his children's birth records call him Pietro, son of Giuseppe.

Now you know he belongs to a father named Giuseppe. But I have 10 Giuseppe Iamarino's in my family tree! Of course I need a Giuseppe who's about the right age to be Pietro's father, but what if I have a few of those? (I do.)

When I examined the facts about my right-aged Giuseppe Iamarinos, one man stood out.

|

| This family makes sense, but I had to track down birth records to prove it. |

Giuseppantonio Iamarino was born in 1819 and married in 1840. That fit with Pietro who was born around 1848. Plus, Pietro named his first son Giuseppantonio—not Giuseppe.

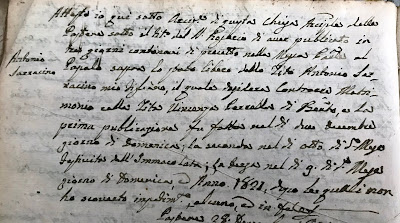

But that is not proof. It's an educated guess at this point. So I attached Pietro to Giuseppantonio, but I added a bookmark and a note to Pietro to remind myself that I needed to prove this relationship. The proof came later when I found Pietro's 1848 birth record.

Use caution when you're piecing together ancestors' families from hundreds of years ago. Naming conventions can offer strong clues—clues that lead to a theory. But the names themselves are not the proof you need.

Use these naming customs to form your theory. Then prove it.

Keep searching for that proof and avoid making a mess of same-named, misplaced people in your family tree.