In 2007 I started ordering Italian vital records on microfilm from FamilySearch.org. The films were from the hometown of one of my grandfathers.

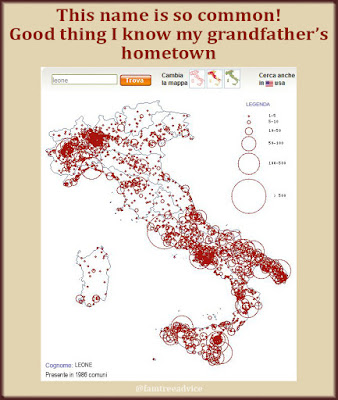

My first goal was to find birth records for my great grandparents to find out their parents' names. But so many people in the town had similar names it was comical. I wasn't sure I was looking at the right family.

There was only one solution. Record every single fact and plug them into my family tree software.

|

| More than 90% of the town is related to me! |

Oh, did I mention I'm Italian?

This work was invaluable. I shared it online with anyone who may have ancestors from my grandfather's town of Basélice. I documented about 16,000 people, and about 15,000 of them are relatives by blood or marriage. Yeah.

Today Italian descendants are gleefully finding their ancestor's documents on FamilySearch.org or the Antenati website. Maybe you've been lucky and found your grandfather's birth record. Maybe you found your great grandparents' marriage record. But are you overlooking entire generations?

This year I used a simple app to download every document available from my ancestral hometowns. Now the organized images are on my computer (and a backup drive) awaiting my analysis.

I'm focusing on my mother's mother's branch first. Despite having grown up with cousins from this branch, I have the least information about them. I cannot get beyond my third great grandparents.

|

| My first visit to Pastene, Sant'Angelo a Cupolo, Italy. |

The solution is going to be extensive, possibly exhaustive documentation of each birth, marriage and death record.

I've begun by finding every child born to my great great grandparents. I'm also documenting the children of my great great grandfather's brother.

The holy grail is that one magical document. The one that includes a baby's grandfather's name. The one that has a baby's maternal uncle as a witness. The one that names the father of a baby's grandmother who is reporting the birth.

I've got to look at each marriage record, too. There may be a marriage between a man and woman whose names I don't recognize. But maybe one is the grandchild of my ancestor. And maybe my ancestor's death record will be included.

Hopefully you enjoy the hunt as much as I do. Perusal of all available documents is the bare minimum.

Complete documentation…priceless.