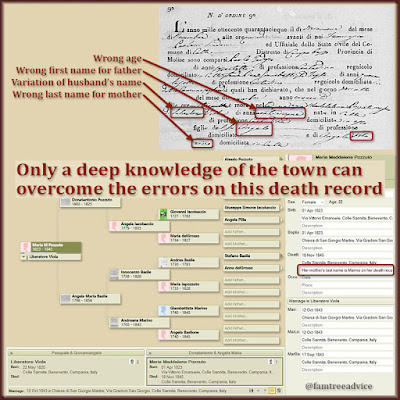

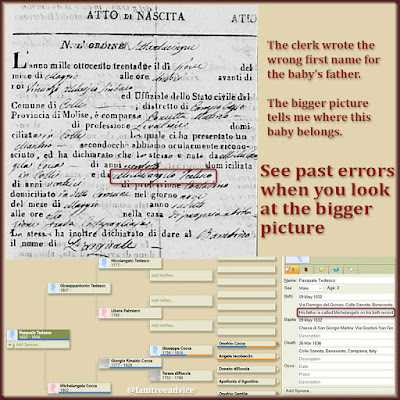

Two weeks ago I explained how I use standardized comments in my family tree file. (See "How to Overcome a Town Clerk's Errors.") If a death record uses the wrong last name for the mother, I use a standard comment. In the description field for the death fact, I enter "Her mother's last name is _____ on her death record."

This shows I'm aware of the error, and I've made sure I've attached this fact to the right person.

One benefit of standardized comments is your family tree software's type-ahead feature. As you begin typing, your software will suggest what you might be about to type. It can save you from having to type the whole phrase.

Spotting Your Typos

That type-ahead feature tends to point out your past mistakes, though. You won't know where you made that typo, but you'll know it's lurking somewhere in your family tree.

There was one place where I kept seeing a past error. I knew the error came from a search-and-replace I did long ago. You see, I'd been entering people's occupations in my tree in Italian for all my Italian nationals. Then it dawned on me that I should include the English translation in parentheses, too.

One search-and-replace error had to do with the Italian word for priest—sacerdote. Somebody in my tree was something called a priest participant, or sacerdote participante. So search-and-replace turned his occupation into "sacerdote (priest) participante." Each time I add another priest by typing "sac," that error taunts me.

Finding Out Who Has the Typo

Now I know how easily I can fix these typos when I spot them. Your family tree's GEDCOM file is the quickest, easiest way to find and fix any typing errors.

|

| Next time you see a typo in any field, use your GEDCOM file to find the culprit. |

A GEDCOM is a text file that uses a standard format any family tree program or website can read. No matter where you build your tree, you can export a GEDCOM.

I opened my GEDCOM file in my favorite text editor and searched for the mistaken priest entry. I found that it happened only once, and it was easy to see which of the 48,853 people in my tree had this error. Next I opened my Family Tree Maker file and went to Benedetto Giampieri's occupation note. I changed "sacerdote (priest) participante" to "sacerdote participante (priest participant)."

Now I'll never see that error again.

Other Uses for the Process

This process came in handy last week. When I add a marriage date to a couple in my tree, and that date came from his, her, or both their birth records, I use one of these standardized comments in the description field:

- From his birth record.

- From her birth record.

- From both their birth records.

Before I decided on which exact phrase to use, I used a couple of variations. Those variations kept showing up as I typed "from his bi," "from her bi," or "from both." I was sick of seeing the variations that had no period, an extra space, or an extra word.

The only way I could see who in my tree was using those variations was to search my GEDCOM. A marriage comment poses an extra challenge in your GEDCOM file. You won't see the names of the bride and groom anywhere near this comment. You'll see their ID numbers instead.

If you see lines like this in your GEDCOM:

1 HUSB @I485@

1 WIFE @I986@

1 MARR From both their birth records.

2 DATE 19 FEB 1900

…go up to the top of your GEDCOM and search for either his ID (@I485@) or hers (@I986@). That'll show you the name of the bride or groom. Then you can go into your family tree to correct the typo you found.

One of my most common typos happens when I don't take my finger off the shift key soon enough. Then I wind up with names like GIovanni, FIlomena, GIuseppe. It happens to me all the time! Now I know I can search my GEDCOM for these misspellings and others, like DOmenico, GIorgio, VIncenzo, and more.

Do you see your past mistakes when you begin typing in your family tree? Are you prone to certain kinds of typos like I am? Let your GEDCOM help you find and eradicate your mistakes forever.