You may have heard that come September 1, 2017, you can no longer order microfilmed records from FamilySearch.org. I didn't think I'd need microfilm anymore since records are being digitized.

But I have one small town in Italy that needs my attention now. So I ordered the microfilm and went to view it at my nearest Family History Center today.

I was focusing on my great grandmother's parents, Antonio Saviano and Colomba Consolazio. I'd hoped to find their births, their marriage, and their parents' names. I had their parents' names only from their own death records. That's not very reliable.

I was disappointed.

This film does contain birth records for two of my great grandmother's brothers. But it does not have her parents' births or marriage.

Grasping for something of value, I scoured each year's index for Saviano or Consolazio. I found two men who may be the brothers of my Colomba Consolazio. I found them on their children's birth records.

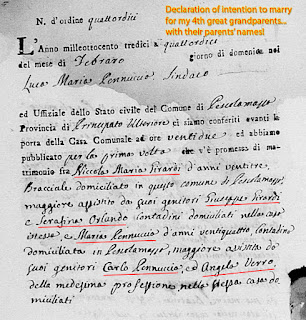

Then I got lucky. One of these potential brothers was Gaetano Consolazio. I found his marriage record and learned his parents' names. And this proved to me that he was my great great uncle.

|

| A reliable source for my third great grandparents' names. |

When my great great grandparents died, their eldest son, Semplicio Saviano, provided the information. He had never met his grandparents. Maybe he didn't know their exact names.

The names I had from Colomba's death record were Semplicio Consolazio and Rafina Zinzaro. The name Semplicio seemed legit because her eldest son was Semplicio. Except I knew she had a baby before him named Raffaele!

Rafina Zinzaro bothered me because Rafina is not a name I've seen before.

The far more reliable source is Gaetano Consolazio's marriage record. His parents, my third great grandparents, were Fiorinto Consolazio and Rufina Zullo who lived in neighboring Santa Paolina.

Gaetano even named his daughter Rufina, so I got to see that unusual name twice. And Fiorinto makes perfect sense to me. You see, I have records from another town showing the birth of my great grandmother and three of her siblings. On two of those documents it says Colomba Consolazio is the daughter of Fiorinto.

I thought those were the mistake. But the less reliable death record contains the mistakes.

So I will score today as a victory.

I'm disappointed not to have found what I wanted. But now I have reason to believe the Consolazio and/or Saviano families lived in Santa Paolina before going to Tufo. The Saviano family then moved to Pastene, where my great grandmother was born.

I have no reason to think they moved because they were given land or something. The fact that they moved twice is even more bizarre.

So I gained some solid information today, along with some leads. I have to quickly decide if I need to order microfilm for the town of Santa Paolina.

The clock is ticking!