Having a purpose and a method to your madness makes genealogy more fun.

What's your genealogy philosophy? Three years ago I started this blog as a way to share my genealogy philosophy.

Your genealogy philosophy is the set of beliefs that guides your genealogy research. For example, you may believe you should research only your direct-line ancestors.

I found that my genealogy philosophy has 4 cornerstones. I hope this causes you to think about your own philosophy.

1. Our Place of Origin is a Part of Us

My parents were born in the U.S. to Italian immigrant fathers and daughters of Italian immigrants. So when I was a child, southern Italian customs and identity were in the very air I breathed.

All my known ancestors came from an area no more than 30 miles wide! Because my roots are so concentrated, I like to harvest every ancestor, cousin, and in-law from the towns' vital records.

The towns my direct ancestors came from are small. The windy roads and rolling hills make it difficult to get from town to town even today.

|

| My ancestors are from neighboring small towns. Almost everyone there is related to me. |

Each town was a world of its own, and its people had a profound influence on my family. That's why I review every vital record from each town. I check to see if and how each person fits into my family tree—and most of them do.

That's why my tree has nearly 23,000 people. Some relationships are way out there. But the peoples' identities matter to me.

It's also important to me to honor my ancestors' culture. I record each person's name as it's written on their birth record.

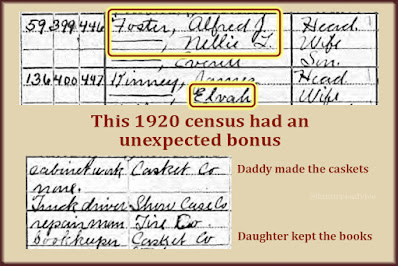

2. The Documents Drive the Story

You may know a lot about your grandparents and great grandparents. But time and time again I see people comment that their ancestors never spoke about the old country. If you're lucky, they may have answered your direct questions about names and places.

But documents can make the difference between family lore and true family history. My ex father-in-law's own mother said her father's brother was the captain of the Titanic. Documents prove that the captain had no brothers!

My grandfather only mentioned having one brother and one sister. It was a funny anecdote because their 3 names translated to Adam, Eve, and Noah. The documents showed me he had another brother and another sister. At least one lived long enough to marry and have children. Why did he leave them out? They actually make the anecdote even better. The 5 siblings' names translate to Adam, Eve, Noah, Mary, and Joseph!

No matter how much your ancestors or the family bible can tell you, the documents can tell you more. That's why I'm driven to gather as many documents as possible.

3. Ancestry Research Has Its Own Best Practices

I've been a corporate website producer for 22 years. Different companies ask for a certain amount of tracking and accountability. As a result, I use spreadsheets for all sorts of things both on the job and off.

So I developed a logical, organized computer filing system for my genealogy documents. And I use spreadsheets to keep track of:

- the documents I've collected (and those I'm missing)

- my direct ancestors' names and Ahnentafel numbers

- translations of Italian occupational words

- my ongoing transcription of my ancestral towns' vital records

Then it dawned on me. If we apply best practices to our research, we'll have fewer incorrect, undocumented family trees. That's why I want to inspire all genealogists to make their family tree their legacy.

4. Consistency Makes All Fact-keeping Better

I have certain routines I follow when I'm adding any document image to my family tree. There are a lot of steps, and I want to do it right. So I make sure I do things the same way each time.

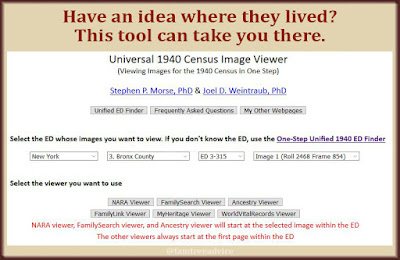

For example, let's say I've discovered a census sheet image for a family in my tree. Here's the routine:

- Download the image to my computer and rename it in the style I've developed.

- Right-click the image and add a title and description in the properties fields. These will carry over when I drag the file into Family Tree Maker.

- I add the image to the head of household and copy it to each member of the household.

- For each person, I add their residence on the date of the census.

- For each person with a job, I add an occupation date, place, and description.

- I note this census for each household member in my document tracker.

It's a lot, but repetition leads to consistency. And when you take care to do it right, you'll have less clean-up to do in the future.

|

| Making a habit of this is one of the best things I ever did for my family tree. |

So there you have my genealogy philosophy. I document everyone with any relationship to me from my ancestral hometowns. I record their facts consistent with their vital records, and I collect as many records for each person as I can. I use some of the same tools I use in business to make my tree more professional. And I'm a stickler for consistency.

If you don't know what your philosophy should focus on, think about why you're doing it and how it makes you feel. What can you do to make yourself feel better about the research and more proud of the results?