|

| These men in my tree had military records for me to find. But not my paternal grandfather. |

09 July 2017

How to Avoid Searching for Non-Existent Genealogy Records

02 July 2017

Does Independence Day Make You Think of Your Ancestors?

- 2nd Lt. Carl C. Sorensen, pilot, Wabasha, Minnesota

- 2nd Lt. Kingsley B. Enoch, co-pilot, Springfield, Massachusetts

- 2nd Lt. Albert L. Berrie, navigator, Belmont, Massachusetts

- 1st Lt. Thomas V. Platten, bombardier, Modesto, California

- T/Sgt. Kenneth E. Sharp, engineer/top turret gunner, Campti, Louisiana

- S/Sgt. Danny Delio, right waist gunner, Mishawaka, Indiana

- S/Sgt. Harold R. Kennelley, radio operator, Spring Mills, Pennsylvania

- S/Sgt. Ernest R. Rossi, left waist gunner, Oakland, California

- S/Sgt. Donald L. Nye, ball turret gunner, Tiffin, Ohio

- S/Sgt. John R. Leone, tail gunner, Bronx, New York

30 June 2017

What Story Does Your Ancestor's Job Tell You?

After visiting the idyllic towns in Italy where my grandfathers were born, I had to wonder why they left their families and came to America.

It turns out their occupations paint two very different pictures. These two stories may represent many immigrants to America.

|

| Our ancestors sought opportunity, work, and a decent living. |

The Skilled Craftsman

My maternal grandfather Adamo left Basélice, Italy twice. The first time he was 23 years old and already listed his occupation as shoemaker. He had two choices:

- Stay in Basélice and be one of a small number of shoemakers in a small town of about 2,000 people.

- Go to New York City and be one of many shoemakers serving thousands of people.

Unfortunately, Adamo's plans were rudely interrupted by World War I. He returned to Italy to fight and became a prisoner of war under brutal circumstances.

Eventually he made his way back to New York City. He continued working as a shoemaker and had his own store in the Bronx for a while. Later he did other types of leather work, making saddles and holsters for the police department.

For Adamo, a skilled young tradesman, coming to America meant greater opportunity doing what he knew how to do.

The Unskilled Laborer

My paternal grandfather Pietro left Colle Sannita, Italy at the age of 18. He had no skilled occupation. He was probably working the land to provide food for his family while his father Francesco made several visits to America for work.

On each of Francesco's trips to work in the United States, he was a laborer. He did whatever type of work was available, including railroad labor and mining.

Pietro did the same as his father, working at a bakery near his uncle's home, at a steel company near his cousin's home, and for the railroad. But he wanted a trade that wasn't so dirty and back-breaking. Oral history tells me that Grandpa's opinion of working in the railroad roundhouse was, "This job stinks on-a the ice."

Pietro became a jewel setter, working with his hands at a clean workbench. He liked it well enough that he kept a small workbench in his cellar at home and continued to make trinkets when I was a girl.

For Pietro, an unskilled laborer, coming to America meant opportunities in fields he might never have imagined.

Just as American families today are likely to relocate for a job at some point in their lives, our ancestors faced a similar situation. While they didn't have an IBM paying to move them to a new state, they did need to move in order to prosper.

It's not hard to understand that reality. Is it?

27 June 2017

Picturing America Through Your Ancestors Eyes

20 April 2017

POW: My Grandfather's World War I Experience

|

| My grandfather Adamo Leone (standing center) in World War I. |

|

| Adamo and family in America. |

11 April 2017

Married Thanks to a Royal Decree

|

| Mariantonia Marucci, age 12…authorized to marry despite her age, by royal decree. |

29 March 2017

Can Genealogy Research Be Painful?

20 March 2017

Why Did They Die?

|

| Can historic events tell you what became of your ancestor? |

17 March 2017

Before Grandpa Came Here, How Did He Get There?

|

| Map of Human Migration |

14 March 2017

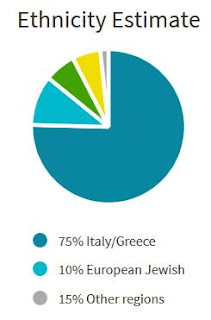

Making Sense of Your DNA Results

|

| My original pie chart and ethnicity estimate from ancestry.com. |

|

| My current pie chart from ancestry.com. |

|

| In the history of things, this area isn't too spread out. |

|

| Results from Family Tree DNA |

11 March 2017

What's Napoleon Got to Do With Italy?

|

| I live on this website 24/7 now. |

20 February 2017

Why Did They Come to America?

- 1851–1860: The Potato Famine in Ireland made emigration a matter of life or death.

- 1861–1870: Prussia and the German states could not provide good jobs to their people.

- 1871–1880: The German Empire, ruled by Otto von Bismarck, became inhospitable to Catholic Germans.

- 1881–1890: Skilled laborers throughout the United Kingdom escaped poverty and famine to work in America's industries.

- 1891–1900: Extreme poverty in Southern Italy, along with malnutrition and disease, led to a massive exodus.

- 1901–1910: Millions of Jews had to leave Russia to escape anti-Semitic violence, army conscription, and ethnic friction.

- The Emergency Quota Act, 1921 restricted immigration from any country to 3% of the number of people from that country living in the US in 1910.

- The Immigration Act of 1924 limited annual European immigration to 2% of the number of people from that country living in the United States in 1890.

- The 1924 Oriental Exclusion Act prohibited most immigration from Asia. That same year the Border Patrol was created to help prevent illegal immigration.

- In 1929 they really clamped down on Asian immigration: The National Origins Formula institutes a quota that caps national immigration at 150,000 and completely bars Asian immigration, though immigration from the Western Hemisphere is still permitted.

26 January 2017

Case Study on "What If There's No There There?"

22 January 2017

What If There's No There There?

|

| Beautiful Pesco Sannita—formerly Pescolamazza. |